by Meg Fluharty

This blog originally appeared on the Mental Elf site on 11th December 2015.

Smoking rates in the US and UK are 2-4 times higher in people with mental illnesses compared to those without (Lasser at al., 2000; Lawerence et al., 2009).

What’s more, smokers suffering from mental illness have higher nicotine dependence and lower quit rates (Smith et al.,2014; Weinberger et al., 2012; Cook et al 2014).

About half of deaths in people with chronic mental illness are due to tobacco related conditions (Callaghan et al., 2014; Kelly et al 2011).

A new ‘state of the art’ review in the BMJ by Tidey and Miller (2015) is therefore much needed, focusing as it does on the treatments currently available for smoking and chronic mental illness, such as schizophrenia, unipolar depression, bipolar depression, anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Methods

Tidey and Miller (2015) identified studies by searching keywords in PubMed and Science Direct, using relevant guidelines, reviews and meta-analyses, and data from the authors’ own files. Two authors reviewed the references and relevant studies were chosen and summarised. Only peer-reviewed articles published in English were reviewed.

It’s important to stress that this was not a systematic review, so the included studies were not graded, but simply summarised with a particular focus on outcomes.

BMJ State of the Art reviews are not systematic reviews, so are susceptible to the same biases as other literature reviews or expert opinion pieces.

Results

Schizophrenia

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) plus psychosocial

Overall, in studies of NRT with psychosocial treatment (such as CBT) 13% of smokers with schizophrenia averaged 6 to 12 month quit rates. Additionally, those continuing to receive NRT had reduced relapse rates.

Bupropion

Studies investigating bupropion in smokers with schizophrenia found initial abstinence, but were followed by high relapse rates with treatment discontinuation, suggesting the need for longer treatment duration. One study found bupropion coupled with NRT and CBT reduced relapse rates.

Varenicline

Studies investigating varenicline in smokers with schizophrenia achieved abstinence at the end of the trial (compared to placebo), but not at 12-month follow up. One study found varenicline and CBT had higher abstinence rates at 52 weeks (compared to controls). Psychiatric side effects reported did not differ between groups, suggesting varenicline is well tolerated in schizophrenia.

Psychosocial

Studies investigating psychosocial treatments in smokers with schizophrenia were varied. Studies implementing CBT displayed high continuous abstinence, and those receiving motivational interviewing were more likely to seek treatment. However, in contingency management trials (receiving monetary reward for abstinence) it appeared individuals might only be staying abstinent long enough for their reward, therefore longer trials are needed.

E-cigarettes

One (uncontrolled) study provided e-cigarettes for 52 weeks to smokers with schizophrenia, finding half reduced their smoking by 50% and 14% quit. None of the participants were seeking treatment for cessation at the start of the trial, suggesting a need for further RCTs of e-cigarettes in smokers with schizophrenia.

The Mental Elf looks forward to reporting on RCTs of e-cigarettes in smokers with schizophrenia.

Unipolar depression

A review of the cessation treatments available to smokers with unipolar depression found little differences in outcomes between individuals with and without depression. However, women with depression were associated with poorer outcomes. Previous studies indicate bupropion, nortriptyline, and NTR with mood management all effective in smokers with depression. Additionally, a long-term study of varenicline displayed continuous abstinence up to 52 weeks without any additional psychiatric side effects.

Bipolar depression

Few studies investigated cessation treatments in smokers with bipolar depression; two small-scale studies of bupropion and varenicline indicated positive results. However a long-term varenicline study found increased abstinence rates at the end of the trial, but not at 6 month follow-up. Some individuals taking varenicline reported suicidal ideation, but this did not differ from the control group.

Anxiety disorders

An analysis investigating both monotherapy and combination psychotherapies found anxiety disorders to predict poor outcomes at follow-up. Despite combination psychotherapy doubling the likelihood of abstinence in non-anxious smokers, neither monotherapy or combination therapy were more effective than placebo in smokers with a lifetime anxiety disorder. However, unipolar and bipolar only touched on pharmaceutical treatments.

PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder)

Studies investigating cessation in PTSD sufferers found higher abstinence rates in integrative care treatment, in which cessation treatment is integrated into pre-existing mental healthcare where therapeutic relationships and a set schedule already exist. A pilot study investigating integrative care with bupropion found increased abstinence at 6 months. However, a contingency management trial found no differences between controls, although it’s possible this was due to small numbers.

Standard treatments to help people quit smoking are safe and effective for those of us with mental illness.

Discussion

Clinical practice should prioritise cessation treatments for individuals suffering mental illnesses, in order to protect against the high rates of tobacco related death and disease in this population.

This review shows that smokers with mental illness are able to make successful quit attempts using standard cessation approaches, with little adverse effects.

Several studies suggested bupropion and varenicline effective in schizophrenia, and varenicline in unipolar and bipolar depression. However, it should be noted, these studies only investigated long-term depression, not situational depression.

Furthermore, all the participants in the studies reviewed were in stable condition, therefore it’s possible outcomes may be different when patients are not as stable. Individuals whom are not stable will have additional psychiatric challenges, may less likely to stick with their treatment regime, and may be more sensitive to relapse.

It should be noted that this was a ‘state of the art’ review, rather than a systematic review or meta-analysis. Therefore- as all literary reviews-it’s subject to bias and limitations, with possible exclusion of evidence, inclusion of unreliable evidence, or not being as comprehensive as if this were a meta analysed. For example, some of the author’s own files are used along side the literary search, but (presumably unpublished) data from other researchers are not sought out or included. Many of the studies included differed in design (some placebo controlled, some compared against a different active treatment ect.) therefore caution should be taken when drawing comparisons across studies.

Additionally, some sections appeared to be much more thorough than others. For example, schizophrenia is covered extensively, including NTR, psychosocial, and pharmaceutical approaches. While all anxiety disorders appeared to be gaped together as one (as opposed to looking at social anxiety, GAD, or panic disorder) and were not explored in detail, drawing little possible treatment conclusions. Finally, this was great literary review, which provided much information, but at times it did feel a bit overwhelming to read and difficult to identify the key information from each sections.

Service users who smoke are being increasingly marginalised, so practical evidence-based information to support quit attempts at the right time is urgently needed.

Links

Primary paper

Tidey JW and Miller ME. Smoking cessation and reduction in people with chronic mental illness. BMJ 2015;351:h4065

Other references

Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, et al. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study.JAMA 2000;284:2606-10 [PubMed abstract]

Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick SR. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health 2009;9:285

Smith PH, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Smoking and mental illness in the US population. Tob Control 2014;23:e147-53.[Abstract]

Weinberger AH, Pilver CE, Desai RA, et al. The relationship of major depressive disorder and gender to changes in smoking for current and former smokers: longitudinal evaluation in the US population. Addiction 2012;107:1847-56. [PubMed abstract]

Cook BL, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, et al. Trends in smoking among adults with mental illness and association between mental health treatment and smoking cessation. JAMA 2014;311:172-82 [PubMed abstract]

Callaghan RC, Veldhuizen S, Jeysingh T, et al. Patterns of tobacco-related mortality among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression. J Psychiatr Res 2014;48:102-10 [PubMed abstract]

Kelly DL, McMahon RP, Wehring HJ, et al. Cigarette smoking and mortality risk in people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2011;37:832-8 [Abstract]

Photo credits

– See more at: http://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/substance-misuse/smoking-and-chronic-mental-illness-whats-the-best-way-to-quit-or-cut-down/#sthash.NvTaK7E6.dpuf

Traumatic brain injury is the leading cause of death and disability among children and young adults worldwide.

Traumatic brain injury is the leading cause of death and disability among children and young adults worldwide. This review highlights a lack of RCTs that explore the potential value of medication for cognitive impairment following traumatic brain injury.

This review highlights a lack of RCTs that explore the potential value of medication for cognitive impairment following traumatic brain injury. Towards the end of last year headlines emerged about captagon, a psychoactive drug “

Towards the end of last year headlines emerged about captagon, a psychoactive drug “ The drug the media are calling captagon

The drug the media are calling captagon  But it is the more long-term, indirect consequences of a sensationalist media discourse that are probably the more harmful ones. The reinforcement of the notion that illegal drugs are one of the main

But it is the more long-term, indirect consequences of a sensationalist media discourse that are probably the more harmful ones. The reinforcement of the notion that illegal drugs are one of the main

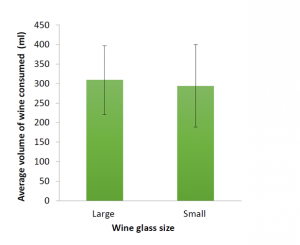

smaller glasses. As this study wasn’t powered to detect a meaningful difference between the two groups, we weren’t really surprised by this finding. However, these pilot data, along with the lessons learned from conducting the study will be used to inform our future research studies and grant applications.

smaller glasses. As this study wasn’t powered to detect a meaningful difference between the two groups, we weren’t really surprised by this finding. However, these pilot data, along with the lessons learned from conducting the study will be used to inform our future research studies and grant applications.