By Michael Dalili @michaeldalili

Over the years, from assessment to analysis, research has steadily shifted from paper to PC. The modern researcher has an ever-growing array of computer-based and online tools at their disposal for everything from data collection to live-streaming presentations of their work. While shifting to computer- or web-based platforms is easier for some areas of research than others, this has proven to work especially well in psychology. These platforms can be used for anything from simply hosting an online version of a questionnaire, to recruiting and testing participants on cognitive tasks. Throughout the course of my PhD, I have increasingly used online platforms for multiple purposes, ranging from participants completing questionnaires online on Bristol Online Survey, to recruiting participants using Amazon Mechanical Turk and completing a task hosted on the Xperiment platform. And I’m not alone! While it’s impossible to estimate just how many researchers are using computer- and web-based platforms to conduct their experiments, we have a better idea of how many researchers are using online crowdsourcing platforms such as Mechanical Turk and Prolific Academic for study recruitment. Spoiler alert: It’s A LOT! In this blog post I will describe these two platforms and give an account of my experiences using them for online testing.

Amazon Mechanical Turk, or MTurk for short, is the leading online crowdsourcing platform. Described as an Internet marketplace for work that requires human intelligence, MTurk was publicly launched in 2005, having previously been used internally to find duplicates among Amazon’s product webpages. It works as follows: workers (more commonly known as “Turkers”), who are individuals who have registered on the service, complete Human Intelligence Tasks (known as HITs) created by Requestors, who approve the completed HIT and compensate the Workers. Prior to accepting HITs, Workers are presented with information about the task, the duration of the task, and the amount of compensation they will be awarded upon successfully completing the task. Right now there are over 280,000 HITs available, ranging widely in terms of the type and duration of task as well as compensation. Amazon claims its Workers number over 500,000 ranging from 190 countries. They can be further sub-divided into “Master Categories”, who are described by Amazon as being “an elite group of Workers who have demonstrated superior performance while completing thousands of HITs across the Marketplace”. At time of writing, there are close to 22,000 Master Workers, with about 3,800 Categorization Masters and over 4,500 Photo Moderation Masters. As you might imagine, some Requestors can limit who can complete their HITs by assigning “Qualifications” that Workers must attain before participating in their tasks. Qualifications can range from requiring Master status to having approved completion of a specific number of HITs. While most Workers are based in the US, the service does boast an impressive gender balance, with about 47% of its users being women. Furthermore, Turkers are generally considered to be younger and have a lower income compared to the general US internet population, but possess a similar race composition. Additionally, many Workers worldwide cite Mechanical Turk as their main or secondary sources of income.

Since its launch, MTurk has been very popular, including among researchers. The number of articles on Web of Science with the search term “Mechanical Turk” has gone from just over 20 in 2012 to close to 100 in 2014 (see Figure 1). A similar search on PubMed produces 15 publications since the beginning of 2015.

However, the popularity of MTurk has not come without controversy. Upon completing a HIT, Workers are not compensated until their task has been “approved” by the Requestor. Should the Requestor reject the HIT, the Worker receives no compensation and their reputation (% approval ratings) decreases. Many Turkers have complained about having had their HITs unfairly rejected, claiming Requestors keep their task data while withholding payment. Amazon has refused to accept responsibility for Requestors’ actions, claiming it merely creates a marketplace for Requesters and Turkers to contract freely and does not become involved in resolving disputes. Additionally, Amazon does not require Requestors to pay Workers according to any minimum wage, and a quick search of available HITs reveals many tasks requiring workers to devote a considerable amount of time for very little compensation. However, MTurk is only one of several crowdsourcing platforms, including CloudCrowd, CrowdFlower, and Prolific Academic.

Launched in 2014, Prolific Academic describes itself as “a crowdsourcing platform for academics around the globe”. Founded by collaborating academics from Oxford and Sheffield, Prolific Academic markets itself specifically as a platform for academic researchers. In fact, until August 2014, registration to the site was limited to UK-based individuals with academic emails (*.ac.uk) until it was opened up to everyone with a Facebook account (for user authentication purposes). Going a step further than its competition in appealing to academic researchers, Prolific Academic offers an extensive list of pre-screening questions (including questions about sociodemographic characteristics, levels of education or certifications, and more) that researchers can use to determine if someone is eligible to complete their study. Therefore, before someone can access and complete their study, they have to answer screening questions selected by the researcher. Individuals who have already completed screening questionnaires (available immediately upon signing up) will only be shown studies they are eligible for under the study page. At the time of writing this blog, according to the site’s homepage there are 5,081 individuals signed up to the site, with over 26,000 data submissions to date. Additionally, the site reports that participants have earned over £26,000 overall thus far. According to the site’s own demographics report from November 2014, 62% of users are male and the average age of users is about 24. Users are predominantly based in the US or UK. However, 1,500 users have joined since this report alone! Unlike MTurk and most other crowdsourcing platforms, Prolific Academic stipulates that researchers must compensate participants appropriately, which they term “Ethical Rewards”, requiring that participants be paid a minimum of £5 an hour.#

I have had experience using both MTurk and Prolific Academic in conducting and participating in research. With the assistance of Dr Andy Woods and his Xperiment platform, where my experimental task is hosted online, I was able to get an emotion recognition task up and running online. This opened up the possibility of studies on larger and more diverse samples, as well as studies being completed in MUCH shorter time frames. With Andy’s help in setting up studies on MTurk, I have run three studies on the platform since July 2014, ranging in sample size from 100 to 243 participants. Most impressively, each study was completed in a matter of hours; conducting the same study in the lab would have taken months! Similarly, given the short duration of these tasks, and the speed and ease of completing and accessing study documents on a computer, these studies cost less than they would have had they been conducted in the lab.

My experience with Prolific Academic has only been as a participant thus far but has been very positive. All the studies I completed have adhered to the “Ethical Rewards” requirement, and all researchers have been prompt in compensating me following study completion. Study duration estimates have been accurate (if anything generous) and compensation is only withheld in the case of failed catch trials (more on that below). The site is very easy to use with a user-friendly interface. It is easy to contact researchers as well, which is helpful for any queries or concerns. I know several colleagues as well who have had similar experiences and I hope to run a study on the platform in the near future.

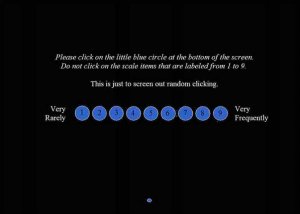

While there have been several criticisms of conducting research on these crowd-sourcing platforms, the most common one amongst researchers is that data acquired this way will be of lesser quality than data from lab studies. Critics argue that the lack of a controlled testing environment, possible distractions during testing, and participants completing studies for compensation as quick as possible without attending to instructions are all reasons against conducting experiments on these platforms. Given the fact that research using catch trials (trials included in experiments to assess whether participants are paying attention or not) has shown failure rates ranging from 14% to 46% in a lab setting, surely participants completing tasks from their own homes would do just as badly, if not worse? We decided to investigate for ourselves. In two of our online studies, we added a catch trial as the study’s last trial, shown below.

Out of the 343 people who completed the two studies, only 3 participants failed the catch trial. That is less than 1% of participants! And we are not the only ones who have found promising results from studies using crowdsourcing platforms. Studies have shown that Turkers perform better on online attention checks than traditional subject pool participants and that MTurk Workers with high reputations can ensure high-quality data, even without the use of catch trials. Therefore, the quality of data from crowdsourcing platforms does not appear to be problematic. However, using catch trials is still a very popular and useful way of identifying participants who may not have completed tasks with enough care or attention.

Since the launch of MTurk, many similar platforms have appeared and advances have been made. MTurk has been used for everything from getting Turkers to write movie reviews to helping with missing persons searches. It’s safe to say that crowdsourcing is here to stay and has changed the way we conduct research online, with many of these sites’ tasks working on mobile and tablet platforms as well. While people have been using computers and web platforms in testing for a long time now, using crowdsourcing platforms for participant recruitment is still in its infancy. Since the launch of MTurk, many similar platforms have appeared and advances have been made. With many new possibilties emerging with the use of these platforms, it is an exciting time to be a researcher.