Amy Campbell, Hannah Sallis & Robyn Wootton

How do you feel about researchers tracking your mood using technology? How about tracking your physical activity or your sleep? How much technology will we let into our lives in the name of research?

These were the questions being asked this summer, when a team of researchers (from Bristol, Manchester, London and Oslo) went to speak to members of the public. They took the University of Bristol’s mobile lab around the city of Bristol and surrounding areas, to festivals, community groups and local parks. They wanted to understand public perceptions towards the use of technology to monitor mood and behaviour throughout the day, whether or not this was acceptable, and how to involve a diverse group of people in their research. In this blog post they tell us about what they did and what they found out.

What are your research interests?

We are an interdisciplinary group of psychologists, epidemiologists, statisticians and digital health researchers. We are interested in the links between health behaviours (such as smoking, alcohol consumption, exercise and sleep) and people’s mental health. To explore this, we usually use large cohort data, such as the Children of the 90s cohort (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/) or the MoBa cohort (https://www.fhi.no/en/studies/moba/). However, health behaviours and mental health are usually only assessed once per year at most, and reports are both retrospective and subjective. So, we have recently become interested in how we can collect better data. We all have smartphones in our pockets and many people wear smartwatches. We wondered whether we should be using wearable technology to collect more detailed real-time data on how health behaviours and mood change throughout the day.

What did you aim to find out from the mobile research lab?

Collecting real time data on mental health is a relatively new approach. As a result, new technologies are emerging and people’s attitudes are evolving. Therefore, before we started collecting data, we first of all wanted to speak with members of the public. We wanted to know if they would prefer using smartphones, smartwatches or smartrings for data collection. We wanted to know how frequently they would be happy to respond to questions and whether they would be happy to wear the devices all day.

We also wanted to speak with a more diverse range of people than usually take part in research. If we expect people to come into the University to speak with us, this will result in a biased sample – usually students or people who happen to live close to the University. Instead, we drove the mobile lab to different areas of Bristol, where people don’t usually take part in research. As a result, we reached a much more diverse group of people than we otherwise would. We hope that by incorporating diverse views into our research at this early stage, it will help us to engage more diverse samples when we come to data collection.

Where did you take the van and who did you speak with?

We headed out in the Bristol Mobile Laboratory with the aim of hearing as many different viewpoints as possible. The first stop was a bustling square in the centre of Bristol on a hot summer’s day. We were ready with a stall full of wearable tech, banners posing interesting questions about our research, and a fridge full of cold drinks. In such a busy location, it wasn’t long until we were chatting to many interested people.

These chats were informal, beginning by explaining our research aims and plans for the study. We were interested in people’s views on the project in general, but also their opinions on the specifics of the study. So, a conversation might begin by asking an open-ended question about people’s thoughts on tracking mood using wearable tech, before asking for feedback on specifics, such as how often people would be willing to answer questions about their mood, or whether there would be any barriers to people wearing the smart watches. Finally, we asked people whether they would be interested in providing their details to be contacted about taking part in this or other studies.

As we wanted to hear from as diverse a group of people as possible, it was important that we didn’t limit our conversations to those who lived in or visited central Bristol. With that in mind, we took the mobile lab on tour, visiting the local park in Keynsham, car boot sales in Hengrove and Marksbury, a coffee morning in Barton Hill, the pier in Weston-Super-Mare, and even made a guest appearance at Knowle West Fest (a local community festival).

These visits to different locations over the course of nine days meant that we spoke to a broad range of people with diverse ages, backgrounds, ethnicities, professions, and life experiences.

What did you find out?

There were many interesting perspectives from the public. We have organised these into those which related to the study design, the devices, and the questions.

- The study

The most important overall finding was that most people we spoke to were really keen to take part and thought our research question was interesting and important. It was really reassuring to know we were on the right track!

- The devices

Next, we were interested in finding out whether people would be happy to wear the devices (e.g., smartwatches, smartrings, other activity monitors). We used ballot boxes so members of the public could vote on their favourites – the rings were a clear winner, followed by the watches. We had some really interesting conversations about wearable technology, with the majority of people seeming keen on using these devices to measure their mood and behaviour.

There was a general feeling that it would be better not to show people their data during the study, people felt that being able to see fluctuations in their mood or their levels of sleep and exercise would influence their subsequent behaviour. Although most people we spoke to said they would like to see their data after the study. We are now working on the best way to return this information, so that it is interesting and useful for our study participants.

We were slightly concerned that we were planning to ask the mood questions too often during the day, and that this might get annoying. Our original plan was to ask 3 times during the day – morning, lunchtime, and evening. Most people we spoke to actually said they’d be happy to answer more frequently than that since it was just for a couple of weeks during the study. We had a couple of people suggest 5 times a day, or even hourly! It was really nice to find out that people were willing to devote so much of their time.

The main limitation that people mentioned around the devices, was that it could restrict people who work in specific roles from taking part in the study. For example, healthcare workers who cannot wear jewellery during their working day would be unable to wear the rings to measure their movement, or to interact with the watches to measure their mood. While these devices are likely to be a useful tool for research, and one that people are keen to use, we need to be mindful of certain groups that could be excluded from our studies as a result. Similarly, we also had several conversations about how we could ensure that older individuals are not excluded from these studies by making the devices easy to use and accessible. Currently we are planning to collect mood data by asking questions via smartwatches. One suggestion was to offer an alternative approach and allow people to hear the questions via pre-recorded phone messages. While this isn’t a viable option for our small feasibility study, this is important to bear in mind for future research.

- The questions

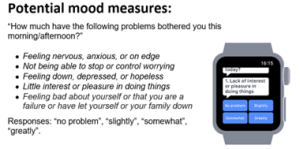

As well as asking people about the devices, we also wanted to get their opinions on the questions we should be asking. Originally, we had suggested using 5 questions to measure mood (these were taken from a 9-item depression questionnaire called the PHQ-9). We printed these questions out to discuss with people, and had some demo watches that ran through these questions.

(Image from Cormack F, McCue M, Taptiklis N, Skirrow C, Glazer E, Panagopoulos E, van Schaik TA, Fehnert B, King J, Barnett JH. Wearable Technology for High-Frequency Cognitive and Mood Assessment in Major Depressive Disorder: Longitudinal Observational Study. JMIR Ment Health 2019;6(11):e12814. doi: 10.2196/12814)

Most people felt the questions were easy to understand, although they didn’t like the first response option ‘no problem’. The question that people liked the least was the final question ‘Feeling bad about yourself or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down’. They felt that if your mood was already low, this question could be quite triggering, especially since all the mood questions were negatively worded. Based on this feedback, we have updated the mood questions, to remove this item and include some positively worded items. We have also updated the response options so that they are easier to interpret (not a lot, a little, a lot, extremely). Based upon feedback, we have also included a single item at the start of the questionnaire, which relates to overall mood: “How are you feeling overall right now?”. Individuals can respond to this item with a smiling face, neutral face or frowning face.

As well as questions on mood, we are interested in what is happening at the time people are responding. Originally, we had planned to ask about whether people had been exercising or sleeping, to check this corresponds with the information we get from the smart ring. Based on discussions while out and about in the van, we have updated this to also include information on significant events that had occurred, and social contact since loneliness came up in discussion multiple times.

One final point that came out of our discussion was that people were really keen to give us as much information as possible. For example, they wanted to be able to explain why they had rated their mood in particular ways – such as the reason for a poor night’s sleep or a significant event. We have now built a small qualitative component into the study, so we can incorporate this information into our findings.

Overall, how did you find the process of gathering public opinions and would you recommend it to other researchers?

We would absolutely recommend that other researchers engage in public involvement, especially trying to speak with as diverse a group as possible. The information we gathered has been extremely valuable in the design of our study, and has enabled us to identify an entirely new group of potential participants. The discussions highlighted several important points that we had not thought of, illustrating the importance of including different perspectives. We thoroughly enjoyed speaking to members of the public, it always reignites your passion for research! We are incredibly grateful to those who gave up their time – our study and results will be richer for this experience.

Affiliations

Amy Campbell is a PhD student in the Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group, at the University of Bristol. Hannah Sallis is a lecturer in the Centre for Academic Mental Health, Bristol Medical School and Robyn Wootton is a research fellow at Nic Waals Institute, Lovisenberg Hospital.

Acknowledgements

We are incredibly grateful to all of the members of the public who gave up their time to tell us their opinions. Their input is incredibly valuable to our future research. Thank you to the whole van team: Rebecca Pearson, Chris Stone, Alexandria Andrayas, Kimberly Beaumont, Ilaria Costantini, Miguel Cordero Vega, Tom Jewell and Nicky Wright, with additional thanks to Andy Skinner and David Kessler for their input on the research plans.

Funding

This work was supported by the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute, University of Bristol, the Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund, grant number 204813/Z/16/Z and a generous donation in memory of Jo Richardson. Robyn Wootton is funded by a postdoctoral fellowship from the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (2020024). Amy Campbell is supported by the Medical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit (MC_UU_00011/7). This work was also supported by the European Research Council (Grant ref: 758813 MHINT).