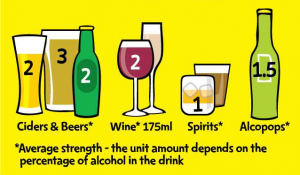

Over the past two years we’ve invited hundreds of people into the lab to drink beer. Unfortunately, we weren’t there to socialise; this was in the name of science. We wanted to know whether giving people information about the number of units and or calories in their beer influenced how much they drank and their perceptions of drinking.

There are strong arguments for including this information: providing unit information may increase knowledge about alcohol consumption and calorie information may help drinkers choose lower calorie (and as a result lower unit) beverages. However, we also wondered whether there might be some unintended consequences of providing this information, particularly for those who are highly motivated to drink. What if unit information simply allows these drinkers to choose higher strength drinks and calorie information only discourages them from eating more, not drinking less? What if discussion around mandatory unit and calorie labelling is distracting us from the bigger issues: health warnings, minimum unit pricing, improving treatment for alcohol dependence and stopping alcohol advertising to young people, to name a few?

So, with this healthy level of scepticism, we set about inviting 264 regular alcohol consumers (mostly undergraduate students) to attend a lab session where they were given some beer and completed some taste ratings. What participants didn’t know was that they had been randomly assigned to one of four conditions. One group had information about the calorie and unit content of the beers, one group just got calorie information, another had just unit information, and the final group got no information at all. As well as measuring how much beer they drank, we also asked participants to reflect on the likely impact of unit and calorie information on their drinking behaviour.

You can read all the results in our (open access) paper that was published this week in the journal Alcohol and Alcoholism. If you want the concise version: we found no evidence that either unit or calorie information influenced how much beer people consumed and we found a lot of variation in the amount people drank.

However, it was our analysis of participants’ thoughts on unit and calorie information that proved vital to understanding what was going on here. Our participants told us that their main motivation for drinking alcohol was usually to get drunk; where unit information was perceived as being helpful, this was to help them choose the highest strength drink. Unit and calorie information was seen as distracting from the social aspect of drinking, and although some participants felt that calorie information might reduce consumption, most thought it would affect others, not themselves. Some people thought that calorie information could be misused by encouraging people to eat less (to compensate), rather than drink less.

It’s interesting that even though the unit and calorie information was very visible in our study (on a piece of paper, presented for 10 minutes), those who had received this information were still very inaccurate when it came to reporting how many units and calories were in their drinks. They basically didn’t seem to have read or engaged with it. If they’re not reading it in this context, is it likely that drinkers will read this information when it’s printed in tiny font on the back of the bottle?

So, what does this all mean for any plans to introduce unit and calorie information? Our study only really tells us about the potential impact of unit and calorie information among young adults (many of whom were students) who tend to drink to get drunk. However, our findings do call into question whether mandatory unit and calorie labelling on its own would reduce how much people drink, and also highlights potential negative unintended consequences of providing this information.

Despite some of these potential unintended consequences, there are still reasons to include unit and calorie information, if only because it’s a consumer right (you know how many calories are in just about everything else you consume). However, perhaps more effort needs to be placed on making this information more engaging and embedding it into public understanding of recommended drinking levels. Coincidentally, an analysis of the public’s awareness of new national alcohol guidelines was also published yesterday. This report argues that although the public have a relatively high awareness of what the guidelines are, they should be put into context by increasing the public’s awareness of the links between alcohol and cancer. Perhaps using health messages such as ‘Drinking alcohol regularly is linked to long-term risks such as cancer’, alongside unit and calorie information, might result in more meaningful changes in attitudes and behaviours around drinking. I feel another study coming on….

Olivia Maynard can be found on Twitter at @OliviaMaynard17

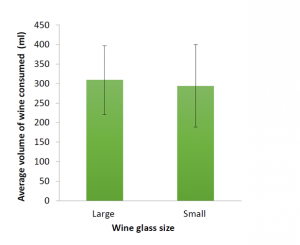

smaller glasses. As this study wasn’t powered to detect a meaningful difference between the two groups, we weren’t really surprised by this finding. However, these pilot data, along with the lessons learned from conducting the study will be used to inform our future research studies and grant applications.

smaller glasses. As this study wasn’t powered to detect a meaningful difference between the two groups, we weren’t really surprised by this finding. However, these pilot data, along with the lessons learned from conducting the study will be used to inform our future research studies and grant applications. e in the UK, from politicians to police, medical specialists to charities, the church and scientists, and addicts and celebrities, with high profile personalities such as Russell Brand and controversial figures such as sacked Government Drugs Advisor Professor David Nutt. The director Arthur Cauty kindly agreed to take part in a question and answer session after the film to discuss his experience making the film and debate the issues raised in the film.

e in the UK, from politicians to police, medical specialists to charities, the church and scientists, and addicts and celebrities, with high profile personalities such as Russell Brand and controversial figures such as sacked Government Drugs Advisor Professor David Nutt. The director Arthur Cauty kindly agreed to take part in a question and answer session after the film to discuss his experience making the film and debate the issues raised in the film.