Written by Katie De-loyde

Back in 2022, a few colleagues and I from the University of Bristol set out to explore a simple but important question:

Could offering a draught alcohol-free beer in pubs and bars reduce how much alcoholic beer people drink?

To find out, we ran a field study in a range of bars and pubs in South West England. You can read about the full study right here: http://bit.ly/3FjygnK

The idea was to see whether giving customers an alcohol-free option on draught would change their drinking behaviour. We were also interested in whether it would affect the venue’s takings, to avoid possible unintended consequences of a well-intended intervention.

Why did we conduct the study?

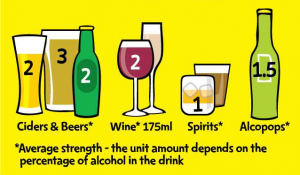

We all know that drinking too much alcohol isn’t great for our health. In fact, excessive alcohol consumption is one of the leading global risk factors for a whole host of serious health issues – everything from liver and heart disease to certain types of cancer (1). The impact stretches far beyond personal health with alcohol-related harm also putting huge pressure on public services like healthcare and the emergency services (2).

So, what can we do about it?

One promising approach is to make alcohol-free and low-alcohol drinks more available in places where people typically drink, like bars and pubs.

The idea is simple: if people have easier access to alcohol-free alternatives, they might choose those options more often, especially in social settings where the act of having a drink can sometimes be just as important as what’s in the drink.

That’s exactly what our study set out to explore. We wanted to see whether adding a draught alcohol-free beer option would make a difference. Would it lead to a drop in alcoholic beer sales? And just as importantly, would it impact the venue’s takings?

What did we do?

To find out, we signed up 14 pubs and bars across South West England. Rather than running a lab experiment or a survey, we went straight to where the action happens: real venues, with real customers, making real choices.

Over an 8-week period, each venue recorded their drink sales, including their draught beer sales. For a total of 4 weeks, it was business as usual: only alcoholic draught beers were available. Then, for another 4 weeks, we made a small but key change: one of the alcoholic draught beers was swapped out for a draught alcohol-free beer.

We then could compare the volume of alcoholic draught beer sales during the draught alcohol-only weeks to the weeks when an alcohol-free draught option was available.

What did we find out and what does this mean?

When the venues added a draught alcohol-free beer to their taps, sales of alcoholic draught beer dropped by around 4 – 5% on average. This equated to 42 – 61 fewer pints of draught alcoholic beer being sold per week across all venues. From a public health perspective, scaling this up to more venues could represent a meaningful shift.

Even more interestingly, this change didn’t hurt the venues financially. In fact, venues actually saw a slight increase in takings, about 1%, during the weeks when the alcohol-free beer was on offer. This increase was small and varied across venues, so may just be statistical noise. However, the important point is that takings did not reduce, which offers reassurance that the venues weren’t penalised financially by offering an alcohol-free option.

What this tells us is important: giving customers a well-placed alcohol-free option leads to lower alcohol consumption without hurting the venue’s takings.

For venue owners, it means a new way to meet customer demand for alternative choices while still protecting profits. And for policymakers, it highlights a simple, real-world intervention that could support broader efforts to reduce alcohol-related harm.

What happened in the first few months after the study?

The study concluded in November 2022, and we were curious to know whether the venues that took part in our study continued offering draught alcohol-free beer once the research had finished. So, in the first few months after the study had ended, we checked in with the venues to find out. At that point, 13 of the original 14 venues were still operating, and nine of them got back to us with updates.

While we were disappointed that a few venues didn’t respond to our update request – possibly introducing a bias in the information we obtained, given that those who didn’t respond may no longer have been offering the alcohol-free draught option – the results were still promising. Of the nine venues that did get back to us, six (67%) confirmed they were still serving alcohol-free draught beer (Figure 1).

Quotes included: (quotes are indicative of conversations with the venues):

Furthermore, the three venues that reported not currently serving alcohol-free draught mentioned that they do bring the alcohol-free draught option back during specific times of the year, such as January. This flexibility indicates that while alcohol-free draught beer might not be a permanent fixture everywhere, venues are tuning in to demand and increasing the availability based on customer demand and seasonal trends.

What happened years later?

Of course, short-term change is one thing, but what about in the long-term? That’s why in 2025 (two and a half years after the study ended), we followed up with venues to see if they still offered the alcohol-free draught beer option.

Of the 11 venues still in operation, seven venues (64%) were permanently offering an alcohol-free draught option (Figure 1). Two other venues were again very postive about the alcohol-free option, stating that they put it back on occasionally (Figure 1).

Quotes included (quotes are indicative of conversations with the venues):

Figure 1. Were the venues still selling alcohol-free beer on draught after the study finished?

- Unknown indicates we were unable to contact the venue and therefore we are unsure as to whether they continued to sell alcohol-free beer on draught after the study.

- Occasionally refers to a venue offering an alcohol-free option on draught at intermitted periods, mainly in the months of January, February, September and / or October. These venues reported seeing the highest demand for alcohol-free choices because of public health initiatives such as Dry January and Sober-October.

These follow-up results are a strong sign that this relatively simple intervention can have a real-world impact. For these venues, alcohol-free beer isn’t just a novelty for designated drivers or a temporary health trend; it’s become a regular part of the lineup.

This kind of sustained adoption matters. It shows that venues can support more mindful drinking habits and keep customers happy, all without sacrificing takings. And with more people looking for balance in how they drink, it’s clear that demand for quality alcohol-free options is here to stay.

That’s a promising takeaway. It shows that alcohol-free draught options have the potential to become a standard part of the offering in venues, especially as more people seek out healthier choices without giving up the social ritual of going out for a drink.

Why did venues agree to take part?

Many of the venues were keen to take part in research to further knowledge in this area, but to offset any possible financial losses associated with taking part (although in the end no financial losses transpired) venues each received a £500 financial incentive.

During the recruitment process, it quickly became clear just how important this incentive was. For many, the idea of offering alcohol-free draught beer had been on their radar before. However, the cost of committing to a full keg of alcohol-free beer, which can be around £100, often held them back.

Our study’s financial incentive gave venues the confidence to take part without the fear of financial loss – whether from not being able to sell the newly purchased keg, or from missing out on profits they might have earned from the alcoholic beer it replaced. The £500 incentive allowed venues to purchase the alcohol-free keg option themselves and still have money left over for any other loses they may incur.

And just out of interest………

We recruited from a list of 433 venues which we sourced via Google Maps and contacts from a previous research project. Armed with email addresses and phone numbers, we started reaching out, one venue at a time. From this list, we were able to recruit 15 venues into the study – a hit rate of 3.5%! One venue later dropped out due to logistics, but overall, it was a solid result driven by alot of persistence and determination!

What’s next?

Looking ahead, the next step is clear: we need more research on the availability of alcohol-free options. By expanding this kind of work to more venues, across different regions, different sociodemographic groups and customer groups, we can build a clearer picture of how alcohol-free options fit into our ever-evolving drinking culture.

Ideally, we would also like to see the units of alcohol being served recorded, not just the volume. This could be calculated at the end of a study, and it would be a more precise measurement of the consumption of alcohol.

Furthermore, it is crucial that we actively promote the findings of this study, as well as any future research, to both the public and the hospitality industry. Highlighting success stories and showcasing venues where these changes have led to positive permanent outcomes can help shift industry perceptions. Additionally, it is important to show businesses that offering alcohol-free alternatives can boost demand and therefore make it easier for others to follow suit. Sharing these insights widely helps normalise the presence of alcohol-free alternatives and demonstrates that there is a growing, legitimate demand for them.

Financial support is just as important. As discussed, some venues may hesitate to offer alcohol-free options due to cost and uncertain demand. Targeted incentives – like subsidised equipment, grants, or further research – could ease that risk and show a real commitment to supporting inclusive, health-conscious options.

Final thoughts

Ultimately, this isn’t just about one study. It’s about helping people make choices that support both their health and lifestyle, while also supporting the businesses that bring communities together. Furthermore, if that future includes more options for everyone at the bar, that is even better!

For bar and pub owners, that’s a win. For policymakers, it’s a compelling case for supporting low- and no-alcohol options and research. And for the rest of us, it’s one more sign that making healthier choices doesn’t have to mean losing out on the things we enjoy.

Acknowledgments

A huge thank you to Claire Garnett, Angela Attwood and Marcus Munafò for their valuable input and support in shaping this blog.

The study would not have been possible without the research team: Jennifer Ferrar, Mark A. Pilling, Gareth J. Hollands, Natasha Clarke, Joe A. Matthews, Olivia M. Maynard, Tiffany Wood, Carly Heath, Marcus R. Munafò and Angela S. Attwood.

This study was funded by the Medical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol; the National Institute for Health and Care Research Bristol Biomedical Research Centre; the Bristol Health Partners Academic Health Science Centre Drug and Alcohol Health Integration Team; and the Behaviour Change by Design collaboration between the University of Bristol and the University of Cambridge. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

The study was supported by the Communities and Public Health People Directorate and the Bristol Nights Project, Bristol City Council.

References

- World Health Organisation. Factors affecting alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm. January 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/alcohol.

- Institute of Alcohol Studies. Alcohol, the emergency services and the criminal justice system. May 2025. Available from: https://www.ias.org.uk/report/alcohol-the-emergency-services-and-the-criminal-justice-system/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

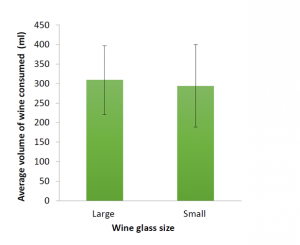

smaller glasses. As this study wasn’t powered to detect a meaningful difference between the two groups, we weren’t really surprised by this finding. However, these pilot data, along with the lessons learned from conducting the study will be used to inform our future research studies and grant applications.

smaller glasses. As this study wasn’t powered to detect a meaningful difference between the two groups, we weren’t really surprised by this finding. However, these pilot data, along with the lessons learned from conducting the study will be used to inform our future research studies and grant applications. e in the UK, from politicians to police, medical specialists to charities, the church and scientists, and addicts and celebrities, with high profile personalities such as Russell Brand and controversial figures such as sacked Government Drugs Advisor Professor David Nutt. The director Arthur Cauty kindly agreed to take part in a question and answer session after the film to discuss his experience making the film and debate the issues raised in the film.

e in the UK, from politicians to police, medical specialists to charities, the church and scientists, and addicts and celebrities, with high profile personalities such as Russell Brand and controversial figures such as sacked Government Drugs Advisor Professor David Nutt. The director Arthur Cauty kindly agreed to take part in a question and answer session after the film to discuss his experience making the film and debate the issues raised in the film.