By Olivia Maynard @OliviaMaynard17

This blog originally appeared on the Mental Elf site on 3rd October 2014

The UK government’s minimum pricing policy for alcohol has been hotly debated over the last couple of years and this week a new study describing the potential benefit of minimum unit pricing over the governments’ current ban on below cost selling has started sparks flying once more.

In the paper, published on Wednesday in the British Medical Journal (BMJ), Brennan and colleagues (2014) use sophisticated modelling to compare the expected effects of the two policies on the following outcomes:

- Alcohol consumption

- Health harms, including deaths, illness, admissions to hospital, quality of life and costs to the NHS

- Drinkers’ expenditure

- Tax and duty revenues

However, before we get our teeth stuck into the study itself, what’s the difference between the two policies?

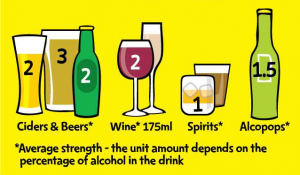

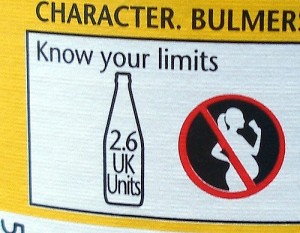

Minimum unit pricing is about setting a floor price (e.g. 45p) for a single unit of alcohol.

Minimum unit pricing (MUP)

- A ‘unit’ of alcohol (roughly half a pint of low strength beer, a measure of spirits or half a regular sized glass of wine) would have to be sold at a set price, such as 45p

- This policy was initially supported in 2012 by the UK government, but was later rejected

- The Scottish government passed legislation to introduce MUP at 50p per unit in June 2012, but as yet this has not been introduced due to a legal challenge from the Scotch Whiskey Association which has now gone all the way to the European Court of Justice. The outcome of this legal challenge is not expected until late 2015

- Canada, Russia and Uzbekistan have all introduced MUP

A ban on below cost selling (BBCS)

- Alcoholic drinks must not be sold for less than the tax payable on the product

- Under this policy, the price of alcohol does not necessarily increase with the strength of the alcohol and for drinks like high strength cider, a unit of alcohol can be sold for as little as 6p under this policy

- The UK government favoured this policy over MUP in 2013 and introduced it in May 2014

The authors answer the following question in their study:

What would the differential potential impact of a BBCS versus a MUP policy of 40p, 45p or 50p if the policies were to be implemented in 2014-2015?

Despite once publicly supporting a minimum unit pricing of 40p. David Cameron’s government has decided instead to put in place a ban on the sale of “below cost” drinks.

Methods

As I said, the authors used some pretty sophisticated modelling techniques (using the Sheffield Alcohol Policy Model [version 2.5]) to answer their research question, but in brief, in order to work out the likely effects of these two alcohol policies, the following information was entered into the model:

- Baseline data on:

- Alcohol consumption for different population subgroups in England (split by sex, age, mean consumption level and income)

- Prices paid for 10 different beverage types and quantity of each purchased, for the different subgroups

- An estimate of the effect that price increases for these 10 beverages would have on consumption levels for the subgroups (given that different subgroups spend and drink different amounts of the 10 beverages)

- The effects of this estimated change in consumption on death and disease rates at one and 10 years post implementation

Results

Given that harmful drinkers are a policy priority group, (consuming on average 58 units for females and 80 for males per week and spending £1,800 and £3,400 per year respectively), the authors focus in particular on the effects of the two policies on this group. Also, whilst MUP at 40p, 45p and 50p were all assessed, I will focus on MUP at 45p, as this is the level initially proposed by the UK government.

Proportion of the market affected by the policies

- Under a BBCS, only 0.7% of all units of alcohol sold in the UK would see a price increase, whilst MUP would affect 23.2% of all units sold

- MUP would disproportionately affect harmful drinkers, increasing the price of 30.5% of the units they purchase, as compared with only 12.5% of units purchased by moderate drinkers

Alcohol consumption

- A BBCS was estimated to reduce the number of units consumed by harmful drinkers by only 3 units per year

- By contrast, MUP was estimated to reduce this by 137 units; a 45-fold reduction as compared with a BBCS

Health harms, including deaths, admissions to hospital, quality of life and costs to the NHS

- The estimated effects on the general population of the two policies after 10 years of implementation are shown below:

|

BBCS |

MUP |

| Annual reduction in number of deaths |

14 |

624 |

| Annual reduction in hospital admissions |

500 |

23,700 |

| Annual reduction in alcohol-related illness |

300 |

12,500 |

| Total number of quality adjusted life years gained |

500 |

24,200 |

| Total saving in healthcare costs |

£9.5 million |

£417.2 million |

- Based on these estimates, MUP will reduce deaths attributable to alcohol by 40 times more than BBCS

- The majority of this harm reduction is likely to be among harmful drinkers, with 89% of the reduction in deaths after 10 years among this group

The study findings suggest that harmful drinkers would be helped most by minimum unit pricing.

Drinkers’ expenditure

- Due to the high price elasticity of alcohol (higher prices mean people lower their consumption to a level which ensures they continue to spend the same amount) neither policy is expected to greatly affect spending

Tax and duty revenues

- A BBCS is estimated to increase revenues in shops and supermarkets by 0.3% (£5.4m)

- By contrast, MUP is estimated to result in a 5.6% (£201.1m) increase in revenues, although the effects on actual profits is unknown

- The effects of the two policies on government tax revenue is small, as although VAT will rise (because this is charged as a percentage of product price and products will be sold at higher prices), alcohol duty revenue will fall (as this is related to the volume of alcohol sold)

Discussion

Professor Alan Brennan, professor of Health Economics and Decision Modelling at the University of Sheffield, who led the study said:

Despite some study limitations we found that a minimum unit price of 45p would be expected to have 40-50 times larger reductions in consumption and health harms.

The limitations Professor Brennan alludes to include the fact that certain assumptions about alcohol price elasticity and actual alcohol consumption and expenditure had to be made in order to run the model. However, the authors state that the sensitivity analyses they have conducted show that the relative scale of the impact of a BBCS versus MUP is robust to these assumptions and uncertainties and, if anything, the scale of the difference is likely to be conservative.

In the editorial accompanying the paper (Stockwell, 2014), Tim Stockwell, the director of the Centre for Addictions Research at the University of British Columbia, Canada, notes that one way to test whether the model is conservative is to compare the model’s predicted effects with actual reported effects in a country where MUP has been introduced. Indeed, when the model is applied to two Canadian provinces with MUP policies, the model underestimates the number of deaths by 2.3 times and the number of hospital admissions by almost 5 times.

It seems therefore that the model is robust enough to assess the effects of the two policies and if anything, underestimates the true likely effect of MUP. These data suggest that MUP would be a far more effective method of reducing consumption and preventing alcohol related harm than the BBCS implemented earlier this year in the UK.

Minimum unit pricing in Canada has been associated with significant reductions in alcohol related harm.

Implications for policy

- The UK government introduced a BBCS in May 2014

- The Scottish legal case will likely pave the way for alcohol pricing policies in other EU jurisdictions interested in introducing MUP, including the Republic of Ireland, Estonia and regional governments in the UK

- Given the potential effectiveness of MUP as compared with a BBCS, the outcome of this legal case is likely to have important implications for public health across Europe

Response from government, industry and others

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this study has not found favour among the alcohol industry, with Miles Beale, Chief Executive of the Wine and Spirits Association arguing that the government should not be “punishing responsible drinkers through higher prices”, a statement which seems at odds with the study’s results which shows that MUP would specifically target harmful drinkers. Indeed, this is what makes MUP different from more indiscriminate policies, such as general price or tax increases, which would indeed punish moderate drinkers.

By contrast, Sir Ian Gilmore, chairman of the Alcohol Health Alliance, warmly received the results of the study and urged Westminster politicians to back the Scottish plans for MUP and “help push it through the European Court of Justice for the good of the public’s health.”

However, the response from the Department of Health was lukewarm, with a spokeswoman reiterating the fact that the government is “taking action to tackle cheap and harmful alcohol such as banning the lowest priced drinks” and noting that the government is “working with industry to promote responsible drinking.”

This close relationship between UK government and the alcohol industry is well documented and alcohol industry lobbying has been cited as the main reason for the government U-turn on MUP in 2013 (Gornall, 2014). Unlike tobacco control policies in the UK, which are protected from the tobacco industry and other commercial interests through a World Health Organisation framework (WHO FCTC, 2005), this is not the case for alcohol policies. John Holmes, a Public Health Research Fellow at the Sheffield Alcohol Research Group, and one of the authors of this study, has previously acknowledged that the alcohol industry should have some say in alcohol policies, but that he is also concerned that the industry is “not particularly interested in . . . engaging in any kind of debate about whether their arguments are accurate. It’s all about creating doubt about what we’re saying.”

Whether the alcohol industry will continue to cast doubt on this research and whether the government will choose to listen to the researchers or the industry, remains to be seen.

In late 2015, the European Court of Justice will decide if the Scottish parliament’s 2012 legislation can be passed, which will have a massive impact on public health in Europe.

Links

Brennan A, Meng Y, Holmes J, Hill-McManus D, Meier PS. (2014). Potential benefits of minimum unit pricing for alcohol versus a ban on below cost selling in England 2014: modelling study. BMJ, 349(g5452).

Gornall J. (2014). Under the influence: 1. False dawn for minimum unit pricing. BMJ 2014;348:f7435.

Stockwell D. (2014). Editorial: Minimum unit pricing for alcohol. BMJ, 349(g5617).

WHO FCTC. (2005). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (PDF). World Health Organisation.

Radu Bercan/Shutterstock.com, Peter Fuchs/Shutterstock.com.

– See more at: http://www.thementalelf.net/mental-health-conditions/substance-misuse/alcohol-minimum-unit-pricing-time-to-take-action/#sthash.hAkkpG2g.dpuf

Towards the end of last year headlines emerged about captagon, a psychoactive drug “

Towards the end of last year headlines emerged about captagon, a psychoactive drug “ The drug the media are calling captagon

The drug the media are calling captagon  But it is the more long-term, indirect consequences of a sensationalist media discourse that are probably the more harmful ones. The reinforcement of the notion that illegal drugs are one of the main

But it is the more long-term, indirect consequences of a sensationalist media discourse that are probably the more harmful ones. The reinforcement of the notion that illegal drugs are one of the main