by Michelle Taylor @chelle_bluebird

From TARG to neuroscience

The final six months of a PhD can be a stressful time. Not only are you trying to write up three years of research, wondering whether you have done enough work, but you also need to consider what to do next. I decided to try my hand at something different…

My PhD was in the area of epidemiology, where I was using large datasets (such as the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, based here at the University of Bristol) to determine causes and consequences of using various drugs of abuse. My time was mainly spent designing and conducting statistical analyses on data that had already been collected and were available for secondary analysis. I completed this work in TARG and the School of Social and Community Medicine and was lucky enough to be funded by the Wellcome Trust on a PhD programme in molecular, genetic and lifecourse epidemiology. The Wellcome Trust also fund two other PhD programmes at the University of Bristol, one in ‘Neural Dynamics’ and another in ‘Dynamic Cell Biology’. Towards the end of my PhD an opportunity arose – the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute were offering three researchers fellowships to conduct nine months of research with one of the other Wellcome Trust programmes. This would involve changing research area and learning something completely new – and I decided to go for it. I applied to move to the Neural Dynamics programme. As my past research had focused on addiction and mental health, gaining knowledge of the field of neuroscience seemed fitting.

After identifying a potential new supervisor and quickly putting together and submitting an application I was told that I had been successful. I was go

ing to become a neuroscientist for the next nine months. The day after handing in my PhD I headed off to the lab of Matt Jones, a neuroscientist whose research interests include sleep, memory and brain circuitry. I was going to be working on a study that aimed to find out more about how genes influence overnight brain activity and memory in humans. I’ve written a little more about this study at the end of this blog post, just in case you’re interested!

My new lab group were very friendly and welcoming, although at times it seemed like they were talking in a different language. I would attend seminars in my new department and be completely confused within minutes. While I did have some knowledge of neuroscience from reading literature, my knowledge was severely lacking compared to that of my new colleagues. Mind you, I could always get my own back by blinding them with statistics!

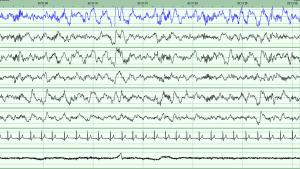

The study involved getting participants to stay in our sleep clinic overnight and measuring their brain activity while they slept. I had to learn new methods of data collection, which involved measuring a person’s head to find specific points and gluing on electrodes to measure their brain activity (known as PSG, or polysomnography) [1]. Once these data were collected, the night’s recording needed to be scored into various stages of sleep. We can determine this from the length, height and frequency of the waves on the sleep recording. There are two main stages of sleep: REM (which stands for rapid eye movement) and non-REM. Non-REM can be broken down further into stages 1, 2 and 3 [2,3]. Stage 3 is the deepest stage of sleep, while stage 2 contains oscillations called spindles and K-complexes which are thought to play a role in memory consolidation while we sleep [3]. Learning to score a night’s sleep was something very new to me. I was used to having my data in the form of numbers in a spreadsheet not as wavy lines dominating the computer screen!

At the end of the nine months, I found myself understanding the talks that I went to – I even started to sound like a neuroscientist myself at times. Many things which originally seemed overwhelming (such as collecting PSG data) now feel like second nature, and the wavy lines on a computer screen are now meaningful. While at first the experience seemed daunting, it has no doubt opened my mind and expanded my knowledge. The ability to conduct interdisciplinary research is a well-regarded asset, but this experience has not only enhanced my CV. It has increased my confidence when talking to other researchers, as I have realised that we can all learn something from one another. Most importantly I have learned to look at research from a broader perspective – what does my research mean for other fields? How can it inform other research that is different from my own? It is, of course, combining the answers to all of these questions that will enhance science and in turn have more impact on the wider world.

My neuroscience experience has come to an end and for now, it is back to epidemiology. But I will definitely look back on my time in neuroscience fondly, and, who knows, I might even get the chance to integrate epidemiological research with neuroscience in the future…

A little more about the study

Different parts of our brains communicate with one another as we learn new information during the day. Overnight brain activity then helps us to file memories for long-term storage. Evidence suggests that this process varies naturally in everyone. To help us understand what causes this variation, we are interested in finding out more about how genes influence overnight brain activity in healthy individuals. Studying our genes by specifically testing those who carry particular (naturally occurring) form of them can help us understand their role in shaping the natural variation we see in brain activity. Importantly, understanding this in healthy people can then go on to help us develop new targets for treatments to help the sick. We therefore carried out a study to look at how naturally occurring variation at a particular gene variant affects memory consolidation during sleep.

The gene variant was chosen based on previous studies that have shown that it affects both brain activity and sleep. To do this, we invited back participants from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children who had provided us with a DNA sample. Information about their genes had been processed and based on this information they were identified as being carriers or non-carriers of the gene we were interested in. This is a study design known as ‘recall-by-genotype’. We then asked these people to spend two nights in a sleep laboratory, perform some memory based tasks and complete some questionnaires so that we can measure how genetic differences relate to memory and brain activity during sleep.

Whilst participants were in the sleep facility we attached a number of sensors to their head in order to record their brain waves, eye movements and muscle activity. We also used sensors on the chest to measure heart rate and take video and audio recordings to confirm whether or not participants become unsettled during the night. Participants were asked to complete some questionnaires about their sleep behaviour and to carry out a memory task before and after sleep.

Whilst participants were in the sleep facility we attached a number of sensors to their head in order to record their brain waves, eye movements and muscle activity. We also used sensors on the chest to measure heart rate and take video and audio recordings to confirm whether or not participants become unsettled during the night. Participants were asked to complete some questionnaires about their sleep behaviour and to carry out a memory task before and after sleep.

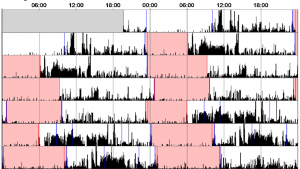

For the two weeks in between visits to the sleep laboratory, we asked participants to wear an ‘actiwatch’. An actiwatch looks like a normal watch and records movement, telling us when the participant usually goes to sleep and wakes up. We asked participants to wear the actiwatch on their wrist at all times and asked them to fill in a sleep diary for the two weeks.

What do we hope to find?

We hope to find that individuals who carry our genetic variant of interest differ from those who do not carry the variant on a range of sleep characteristics including the non-REM stage 2 spindles and slow wave oscillations found on stage 3 of non-REM sleep. We also expect to find difference between genotype groups on ability to complete the memory task, and the speed at which they complete the memory task. Finally, we expect to observe a correlation between the stage 2 sleep spindles and the results of the memory task. If we observe these results in our data, then this will suggest that this genotype can influence brain activity during sleep which then in turn can effect a person’s memory, as this memory is not being consolidated as well over night.

We hope to find that individuals who carry our genetic variant of interest differ from those who do not carry the variant on a range of sleep characteristics including the non-REM stage 2 spindles and slow wave oscillations found on stage 3 of non-REM sleep. We also expect to find difference between genotype groups on ability to complete the memory task, and the speed at which they complete the memory task. Finally, we expect to observe a correlation between the stage 2 sleep spindles and the results of the memory task. If we observe these results in our data, then this will suggest that this genotype can influence brain activity during sleep which then in turn can effect a person’s memory, as this memory is not being consolidated as well over night.

Where can I find out more?

A protocol for this study has already been published [4].

Once completed, this study will be published open access within a scientific journal.

References:

[1] Wikipedia – polysomnography

[2] American association of sleep

[3] Wikipedia – sleep (including information on stages, spindles, K-complexes and slow waves)

[4] Hellmich C, Durant C, Jones MW, Timpson NJ, Bartsch U, Corbin LJ (2015) Genetics, sleep and memory: a recall-by-genotype study of ZNF804A variants and sleep neurophysiology. BMC Med Genet 16:96

Nine months later I was on my way to Heathrow for a two month stint collecting data on a cannabis administration study. I was both excited and apprehensive. I have never lived more than a 3 hour drive away from family, and have always been in a city where I have known people. I didn’t know whether I would get homesick, or whether I would make friends on my trip abroad. These feelings of apprehension soon disappeared in the first few hours of my first day at the New York Psychiatric Institute. Everyone I met was so friendly and welcoming, even the many morning commuters who stopped to help the lone Brit who was obviously puzzled by the subway map at 7.30am.

Nine months later I was on my way to Heathrow for a two month stint collecting data on a cannabis administration study. I was both excited and apprehensive. I have never lived more than a 3 hour drive away from family, and have always been in a city where I have known people. I didn’t know whether I would get homesick, or whether I would make friends on my trip abroad. These feelings of apprehension soon disappeared in the first few hours of my first day at the New York Psychiatric Institute. Everyone I met was so friendly and welcoming, even the many morning commuters who stopped to help the lone Brit who was obviously puzzled by the subway map at 7.30am. I was to spend the next six weeks collecting data for a study examining the neuro-behavioural mechanisms of decisions to smoke cannabis at the Substance Use Research Center in the New York Psychiatric Institute at Columbia University. This research centre is unique; it is one of the largest drug administration centre in the world and has licenses to administer a wide variety of drugs, including cannabis, cocaine and heroin. This means that much of the research conducted here is cutting edge. The aim of the study that I would be working on was to shed light on how and why drug abusers repeatedly make decisions to take drugs despite substantial negative consequences. The study used brain imaging (fMRI) to examine the neural and behavioural processes involved in decisions to self-administer cannabis, compared to decisions to eat food, in regular cannabis users. We also examined the influence of drug and food cues on the processes underlying these decisions. To do this, participants were recruited as inpatients and stayed with us in the lab for a week. Data collection for this study is still ongoing, but I will be sure to write another blog post with what we found when the results are available.

I was to spend the next six weeks collecting data for a study examining the neuro-behavioural mechanisms of decisions to smoke cannabis at the Substance Use Research Center in the New York Psychiatric Institute at Columbia University. This research centre is unique; it is one of the largest drug administration centre in the world and has licenses to administer a wide variety of drugs, including cannabis, cocaine and heroin. This means that much of the research conducted here is cutting edge. The aim of the study that I would be working on was to shed light on how and why drug abusers repeatedly make decisions to take drugs despite substantial negative consequences. The study used brain imaging (fMRI) to examine the neural and behavioural processes involved in decisions to self-administer cannabis, compared to decisions to eat food, in regular cannabis users. We also examined the influence of drug and food cues on the processes underlying these decisions. To do this, participants were recruited as inpatients and stayed with us in the lab for a week. Data collection for this study is still ongoing, but I will be sure to write another blog post with what we found when the results are available. I found this research fascinating and it was a pleasure to be involved in the work carried out in this department. The experience was made even more enjoyable by the people I was working with. There were many office conversations about the British and American slang that was being used, many lunchtime trips to Chipotle (an American fast food restaurant that I am definitely missing since my return to the UK), and several Friday evening trips to the local Irish bar. One office memory that will always stick in my mind was meeting a very accomplished researcher in the field of my PhD, a researcher that was definitely someone I should be impressing. Upon entering this individuals office on an extreme

I found this research fascinating and it was a pleasure to be involved in the work carried out in this department. The experience was made even more enjoyable by the people I was working with. There were many office conversations about the British and American slang that was being used, many lunchtime trips to Chipotle (an American fast food restaurant that I am definitely missing since my return to the UK), and several Friday evening trips to the local Irish bar. One office memory that will always stick in my mind was meeting a very accomplished researcher in the field of my PhD, a researcher that was definitely someone I should be impressing. Upon entering this individuals office on an extreme I did, of course, take every opportunity to explore New York. I was lucky enough to get tickets to watch the New York Yankees beat the Boston Red Sox at the Yankee Stadium, which was also one of the last games played by baseball-legend Derek Jeter. I made several trips to the American Natural History Museum (my favourite type of museum, and this one cannot be done in a day), and while there saw a live spider show, a 3D film about Great White Sharks and a full T-Rex skeleton. The glorious weather allowed for several leisurely strolls around Central Park. And, of course, the American food definitely needs a mention. If anyone reading this takes a trip over the Atlantic, I would definitely recommend visiting Big Daddy’s Diner for what could be the best milkshake on the planet. And don’t be shy about trying a hotdog from one of the carts that can be found on nearly every street corner. The reason there are so many of them is that they’re delicious! I would also recommend a trip to the Russian Tea Rooms for caviar afternoon tea, an evening at the New York Metropolitan Opera (if that’s your cup of tea), and a trip to Coney Island.

I did, of course, take every opportunity to explore New York. I was lucky enough to get tickets to watch the New York Yankees beat the Boston Red Sox at the Yankee Stadium, which was also one of the last games played by baseball-legend Derek Jeter. I made several trips to the American Natural History Museum (my favourite type of museum, and this one cannot be done in a day), and while there saw a live spider show, a 3D film about Great White Sharks and a full T-Rex skeleton. The glorious weather allowed for several leisurely strolls around Central Park. And, of course, the American food definitely needs a mention. If anyone reading this takes a trip over the Atlantic, I would definitely recommend visiting Big Daddy’s Diner for what could be the best milkshake on the planet. And don’t be shy about trying a hotdog from one of the carts that can be found on nearly every street corner. The reason there are so many of them is that they’re delicious! I would also recommend a trip to the Russian Tea Rooms for caviar afternoon tea, an evening at the New York Metropolitan Opera (if that’s your cup of tea), and a trip to Coney Island. Although it was daunting going abroad for that length of time to begin with, I don’t think I would be having those feelings again and I would definitely jump at any opportunity to work in a different environment in the future. I am very grateful that I am a PhD student in a large working group like TARG, as without this I probably would not have come across opportunities such as this one. This experience has taught me the importance of inter-disciplinary research, and the need for several fields contributing evidence to a much larger research question. Since this trip, I have been successful in a fellowship application allowing me 9 months in a different department at the University of Bristol, an application that I probably would not have made if it wasn’t for my experience at the Columbia University. I am an epidemiologist and do not have any plans to change that; however I do plan to conduct more interdisciplinary research in the future. I would like to that Gill (and everyone in her lab group) for welcoming me and making this trip possible. I look forward to hopefully working with you again in the future…

Although it was daunting going abroad for that length of time to begin with, I don’t think I would be having those feelings again and I would definitely jump at any opportunity to work in a different environment in the future. I am very grateful that I am a PhD student in a large working group like TARG, as without this I probably would not have come across opportunities such as this one. This experience has taught me the importance of inter-disciplinary research, and the need for several fields contributing evidence to a much larger research question. Since this trip, I have been successful in a fellowship application allowing me 9 months in a different department at the University of Bristol, an application that I probably would not have made if it wasn’t for my experience at the Columbia University. I am an epidemiologist and do not have any plans to change that; however I do plan to conduct more interdisciplinary research in the future. I would like to that Gill (and everyone in her lab group) for welcoming me and making this trip possible. I look forward to hopefully working with you again in the future…