Vicky Carlisle, who completed her PhD in TARG in 2021 has recently been interviewed about her research for the University of Bristol podcast. In the podcast, Vicky discusses her non-traditional route into academia as well as her research on the multi-level influences on recovery within opioid substitution treatment (OST). Vicky discusses the role of stigma and trauma as important barriers to recovery and retention in OST and her plans for developing an intervention to address stigma in OST

Category: Uncategorized

Involving the Public in Research: Taking the Mobile Lab on the Road

Amy Campbell, Hannah Sallis & Robyn Wootton

How do you feel about researchers tracking your mood using technology? How about tracking your physical activity or your sleep? How much technology will we let into our lives in the name of research?

These were the questions being asked this summer, when a team of researchers (from Bristol, Manchester, London and Oslo) went to speak to members of the public. They took the University of Bristol’s mobile lab around the city of Bristol and surrounding areas, to festivals, community groups and local parks. They wanted to understand public perceptions towards the use of technology to monitor mood and behaviour throughout the day, whether or not this was acceptable, and how to involve a diverse group of people in their research. In this blog post they tell us about what they did and what they found out.

What are your research interests?

We are an interdisciplinary group of psychologists, epidemiologists, statisticians and digital health researchers. We are interested in the links between health behaviours (such as smoking, alcohol consumption, exercise and sleep) and people’s mental health. To explore this, we usually use large cohort data, such as the Children of the 90s cohort (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/) or the MoBa cohort (https://www.fhi.no/en/studies/moba/). However, health behaviours and mental health are usually only assessed once per year at most, and reports are both retrospective and subjective. So, we have recently become interested in how we can collect better data. We all have smartphones in our pockets and many people wear smartwatches. We wondered whether we should be using wearable technology to collect more detailed real-time data on how health behaviours and mood change throughout the day.

What did you aim to find out from the mobile research lab?

Collecting real time data on mental health is a relatively new approach. As a result, new technologies are emerging and people’s attitudes are evolving. Therefore, before we started collecting data, we first of all wanted to speak with members of the public. We wanted to know if they would prefer using smartphones, smartwatches or smartrings for data collection. We wanted to know how frequently they would be happy to respond to questions and whether they would be happy to wear the devices all day.

We also wanted to speak with a more diverse range of people than usually take part in research. If we expect people to come into the University to speak with us, this will result in a biased sample – usually students or people who happen to live close to the University. Instead, we drove the mobile lab to different areas of Bristol, where people don’t usually take part in research. As a result, we reached a much more diverse group of people than we otherwise would. We hope that by incorporating diverse views into our research at this early stage, it will help us to engage more diverse samples when we come to data collection.

Where did you take the van and who did you speak with?

We headed out in the Bristol Mobile Laboratory with the aim of hearing as many different viewpoints as possible. The first stop was a bustling square in the centre of Bristol on a hot summer’s day. We were ready with a stall full of wearable tech, banners posing interesting questions about our research, and a fridge full of cold drinks. In such a busy location, it wasn’t long until we were chatting to many interested people.

These chats were informal, beginning by explaining our research aims and plans for the study. We were interested in people’s views on the project in general, but also their opinions on the specifics of the study. So, a conversation might begin by asking an open-ended question about people’s thoughts on tracking mood using wearable tech, before asking for feedback on specifics, such as how often people would be willing to answer questions about their mood, or whether there would be any barriers to people wearing the smart watches. Finally, we asked people whether they would be interested in providing their details to be contacted about taking part in this or other studies.

As we wanted to hear from as diverse a group of people as possible, it was important that we didn’t limit our conversations to those who lived in or visited central Bristol. With that in mind, we took the mobile lab on tour, visiting the local park in Keynsham, car boot sales in Hengrove and Marksbury, a coffee morning in Barton Hill, the pier in Weston-Super-Mare, and even made a guest appearance at Knowle West Fest (a local community festival).

These visits to different locations over the course of nine days meant that we spoke to a broad range of people with diverse ages, backgrounds, ethnicities, professions, and life experiences.

What did you find out?

There were many interesting perspectives from the public. We have organised these into those which related to the study design, the devices, and the questions.

- The study

The most important overall finding was that most people we spoke to were really keen to take part and thought our research question was interesting and important. It was really reassuring to know we were on the right track!

- The devices

Next, we were interested in finding out whether people would be happy to wear the devices (e.g., smartwatches, smartrings, other activity monitors). We used ballot boxes so members of the public could vote on their favourites – the rings were a clear winner, followed by the watches. We had some really interesting conversations about wearable technology, with the majority of people seeming keen on using these devices to measure their mood and behaviour.

There was a general feeling that it would be better not to show people their data during the study, people felt that being able to see fluctuations in their mood or their levels of sleep and exercise would influence their subsequent behaviour. Although most people we spoke to said they would like to see their data after the study. We are now working on the best way to return this information, so that it is interesting and useful for our study participants.

We were slightly concerned that we were planning to ask the mood questions too often during the day, and that this might get annoying. Our original plan was to ask 3 times during the day – morning, lunchtime, and evening. Most people we spoke to actually said they’d be happy to answer more frequently than that since it was just for a couple of weeks during the study. We had a couple of people suggest 5 times a day, or even hourly! It was really nice to find out that people were willing to devote so much of their time.

The main limitation that people mentioned around the devices, was that it could restrict people who work in specific roles from taking part in the study. For example, healthcare workers who cannot wear jewellery during their working day would be unable to wear the rings to measure their movement, or to interact with the watches to measure their mood. While these devices are likely to be a useful tool for research, and one that people are keen to use, we need to be mindful of certain groups that could be excluded from our studies as a result. Similarly, we also had several conversations about how we could ensure that older individuals are not excluded from these studies by making the devices easy to use and accessible. Currently we are planning to collect mood data by asking questions via smartwatches. One suggestion was to offer an alternative approach and allow people to hear the questions via pre-recorded phone messages. While this isn’t a viable option for our small feasibility study, this is important to bear in mind for future research.

- The questions

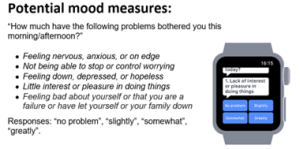

As well as asking people about the devices, we also wanted to get their opinions on the questions we should be asking. Originally, we had suggested using 5 questions to measure mood (these were taken from a 9-item depression questionnaire called the PHQ-9). We printed these questions out to discuss with people, and had some demo watches that ran through these questions.

(Image from Cormack F, McCue M, Taptiklis N, Skirrow C, Glazer E, Panagopoulos E, van Schaik TA, Fehnert B, King J, Barnett JH. Wearable Technology for High-Frequency Cognitive and Mood Assessment in Major Depressive Disorder: Longitudinal Observational Study. JMIR Ment Health 2019;6(11):e12814. doi: 10.2196/12814)

Most people felt the questions were easy to understand, although they didn’t like the first response option ‘no problem’. The question that people liked the least was the final question ‘Feeling bad about yourself or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down’. They felt that if your mood was already low, this question could be quite triggering, especially since all the mood questions were negatively worded. Based on this feedback, we have updated the mood questions, to remove this item and include some positively worded items. We have also updated the response options so that they are easier to interpret (not a lot, a little, a lot, extremely). Based upon feedback, we have also included a single item at the start of the questionnaire, which relates to overall mood: “How are you feeling overall right now?”. Individuals can respond to this item with a smiling face, neutral face or frowning face.

As well as questions on mood, we are interested in what is happening at the time people are responding. Originally, we had planned to ask about whether people had been exercising or sleeping, to check this corresponds with the information we get from the smart ring. Based on discussions while out and about in the van, we have updated this to also include information on significant events that had occurred, and social contact since loneliness came up in discussion multiple times.

One final point that came out of our discussion was that people were really keen to give us as much information as possible. For example, they wanted to be able to explain why they had rated their mood in particular ways – such as the reason for a poor night’s sleep or a significant event. We have now built a small qualitative component into the study, so we can incorporate this information into our findings.

Overall, how did you find the process of gathering public opinions and would you recommend it to other researchers?

We would absolutely recommend that other researchers engage in public involvement, especially trying to speak with as diverse a group as possible. The information we gathered has been extremely valuable in the design of our study, and has enabled us to identify an entirely new group of potential participants. The discussions highlighted several important points that we had not thought of, illustrating the importance of including different perspectives. We thoroughly enjoyed speaking to members of the public, it always reignites your passion for research! We are incredibly grateful to those who gave up their time – our study and results will be richer for this experience.

Affiliations

Amy Campbell is a PhD student in the Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group, at the University of Bristol. Hannah Sallis is a lecturer in the Centre for Academic Mental Health, Bristol Medical School and Robyn Wootton is a research fellow at Nic Waals Institute, Lovisenberg Hospital.

Acknowledgements

We are incredibly grateful to all of the members of the public who gave up their time to tell us their opinions. Their input is incredibly valuable to our future research. Thank you to the whole van team: Rebecca Pearson, Chris Stone, Alexandria Andrayas, Kimberly Beaumont, Ilaria Costantini, Miguel Cordero Vega, Tom Jewell and Nicky Wright, with additional thanks to Andy Skinner and David Kessler for their input on the research plans.

Funding

This work was supported by the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute, University of Bristol, the Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund, grant number 204813/Z/16/Z and a generous donation in memory of Jo Richardson. Robyn Wootton is funded by a postdoctoral fellowship from the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (2020024). Amy Campbell is supported by the Medical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit (MC_UU_00011/7). This work was also supported by the European Research Council (Grant ref: 758813 MHINT).

TARG’s top tips for wellbeing and productivity

Working from home can present huge challenges both to our work productivity and overall wellbeing. These challenges will vary in type and intensity from one person to another, and may also wax and wane at different times of the year.

Things we in TARG have been struggling with include:

- No separate workspace versus home space; blurring of boundaries between home and work

- Lack of motivation due to general stress or anxiety about the state of the world

- Material problems e.g. caring responsibilities, things in life disrupted by the pandemic

- The social aspect of not seeing people

- Difficulties in communicating and getting things done when we can’t be together in person

Although it is important to note that “it’s ok not to be ok”, there are things we can do that may help us feel better and/or be more productive in our work during these times.

With this in mind, and wanting to support each other as best we can, our group got together to share tips for coping with working from home.

Here is the TARG list of top tips for wellbeing and productivity:

Working Environment

- Set a designated working area and go to a separate space for breaks.

- Or, rotate your working area around different spaces for a change of scene.

- Keep your working environment tidy.

- It helps if you keep your home tidy too – it doesn’t have to be spotless though! Just things like making the bed and opening the curtains each morning helps.

- Have one day every week or fortnight when you tidy up your files and emails.

- If it helps you concentrate, listen to music or nature sounds or have the radio on. You could turn it off when you’re on a break, then restart it when you want to continue working. Spotify has lots of focus music playlists, or try YouTube.

- Try using earplugs or noise-cancelling headphones if you want a quieter environment.

- If you have to work from a laptop, try attaching a computer monitor and separate keyboard and mouse. The extra monitor extends your screen space making working easier, and also gives the feeling of using a separate ‘work computer’ helping to differentiate your personal laptop use from work time.

- Download a second web browser and use it only for work tasks. Keep only work bookmarks on your work web browser.

Emails

- Only check your emails two to three times a day at specific times.

- Add a message to your email signature such as “I check my email at 10am and 3pm every day so you will only hear from me at these times”. We don’t have to be constantly available.

- Don’t leave your email inbox open. Turn off notification sounds and popups.

- Work for an hour in the morning before checking emails.

- Glance at an email to see if it’s important but then ignore it until later.

- Flag emails and then answer them all in a block of time later.

Phone

- Only check your phone two to three times a day at specific times.

- Leave your phone out of sight e.g. in a drawer that’s out of reach.

- Turn off notification sounds.

- Remove work email apps from your phone.

Daily Routine

- Tailor your work schedule to your personal preferences – there’s no need to stick to 9 to 5.

- Whatever your preferred working schedule is, do have one, and stick to it.

- Schedule tea breaks at certain times of the day.

- Get ready and dress in the morning as if you were going to work.

- Go for a quick walk before you start work to simulate a commute.

- Have a proper lunch break, away from your working area if you can.

Task Scheduling

- ‘Eat the frog’: do the most difficult task of the day first.

- Block out a particular day for particular tasks.

- Schedule tasks that require more concentration to quieter times of the day.

- Set your tasks for the day each morning. Make them specific goals. Prioritise the tasks you need to do; don’t try to do everything.

- Or, schedule tasks per week rather than per day. Whatever works for you.

- If you’re struggling to start try to do just one task. Often once you start it’s easier to continue.

- Break up big tasks into smaller chunks and schedule them through the week.

- Make your day task-based rather than hours-based. E.g., “I will complete three tasks today” rather than “I will work seven hours today.” If you finish early, have the rest of the day off!

To Do and Done Lists

- Keep a ‘Done’ list to remind yourself of what you’ve achieved each day.

- If you start a task but haven’t finished it, have a symbol you can mark next to it so you can still see your progress.

- Have a symbol/colour to mark tasks that you’re waiting to hear back from others on before you can proceed.

- Colour code your to do list depending on task urgency.

- Break down tasks into micro-steps.

- Make your to do list visually appealing.

- Use Trello to make a to do list.

Motivation/Rewards

- Schedule time for activities you enjoy.

- Write a list of things you enjoy and use it as motivation.

- Gamify work: time spent working unlocks points that you can spend on fun/relaxing activities or treats. You could make a motivation board with stickers to record your points.

Meetings

- During meetings which are mostly just listening, do household chores that don’t take mental capacity (so you can still concentrate on listening) to have extra free time later.

- Attend a meeting from outside by using your phone. Sit in the garden, or go for a walk.

Maintain Clarity and Perspective

- Avoid foods at lunchtime that spike your blood sugar leading to lethargy in the afternoon.

- If things pop into your head (e.g. things to do, worries) note them down and set them aside for later.

- If you’re struggling to focus, take a break. E.g. go for a walk, have a nap or relax with a book. Set a timer for going back to work.

- Take a break every 10 minutes or use the Pomodoro Technique.

- Set a time limit for tasks and then move on (unless it’s urgent that you finish it).

- If you’re struggling to get anything done, sometimes it’s much better to just do the minimum amount and then stop, or allow yourself the day off and try again tomorrow. That’s ok!

- If you have a non-productive day, don’t be hard on yourself. Try speaking to yourself as you would a dear friend.

- We are all trying to just be as reasonably productive and motivated as we can in these circumstances – don’t expect as much from yourself as you would in normal times, and know that you are most definitely not alone in struggling.

Take Care of your Wellbeing

- Looking after your wellbeing is important in and of itself but also benefits productivity.

- There are lots of things we can do to improve our wellbeing, but we don’t want to turn those things into yet more ‘tasks to get done’. Rather than setting wellbeing goals, you could try simply recording what you do each day for your wellbeing, without judgment or expectation. By just recording these things, you may find you automatically start doing them more.

- Move: go for a walk, do some stretches, get up to make a cup of tea, walk around the garden.

- Sleep: try to get plenty of sleep, instead of working late ask yourself “can this task be finished tomorrow?”

- Rest: set aside a bit of time each day to rest and relax with whatever feels restful to you.

- Play: find time to do things you enjoy, having fun is important for adults as well as children!

- Gratitude: take a moment to think about something you are grateful for in your life.

- Nature: notice the nature all around us, even in urban environments there is plenty to see and hear.

- Pets: cuddling a pet releases endorphins!

- Laugh: listen to a funny podcast or watch a comedy show.

- Connect: share how you really feel with a trusted person. Resist the urge to pretend everything’s ok if it’s not. (But if you don’t feel like sharing, that’s ok too.)

Group Strategies

- Daily morning check-ins that anyone can pop in to.

- Socials (socially distanced outside when permitted by rules, otherwise online).

- Online coffee breaks and lunch breaks on Slack/Zoom.

- Continuing the schedule of regular meetings that we had before the pandemic, but online.

- Sharing our successes AND failures, it’s especially good if we can laugh about it!

- Using Slack for quick messages and to stay in touch socially with a dedicated social channel.

- One-to-one catch ups.

- Sharing goals for the day with each other and checking in at the end of the day/an hour later.

- Online writing retreats.

Incorporating new things into your daily routine can feel odd or an uphill struggle at first, but we humans are very good at building habits, so stick with it for a few days and it might become second nature. You could try picking one or two things from the list that resonate with you, and see how you go.

Thanks to the whole group for their contributions and especially to Jackie Thompson for holding the group meeting and co-ordinating responses.

We will be posting these tips on Twitter; if you’d like to see these regular reminders in your Twitter feed follow @BristolTARG or head to the #TARGWellbeing hashtag.

Take care everyone!

Improving the way research is done: the UK Reproducibility Network

Written by Natalie Hunter, Graduate Trainee – Research Landscape at Wellcome Trust

As a graduate at Wellcome, I get the opportunity to be involved in so many exciting initiatives, including working with the people aiming to tackle some of the biggest challenges in science and research.

Attending the first annual meeting of the UK Reproducibility Network (UKRN) last Friday is a great example of this. UKRN is a grassroots, researcher-led organisation with the aim of improving scientific integrity, with a particular focus on the reproducibility of research. There’s been a lot written about the so-called ‘reproducibility crisis’ in research recently, but it essentially boils down to this: were the experiments conducted in a non-biased way, blinded where possible? Have all of the results been reported – including negative ones? Were appropriate controls used? Could the study be repeated by somebody else and the same results be found? However, it has become increasingly obvious that a number of papers, some with very influential results, have not been conducted to this standard. For example in some areas such as preclinical cancer research, studies estimate as many as 70-90% of papers have irreproducible results. This links to the wider problem of research culture we’ve identified and are working on here at Wellcome.

UKRN was founded to increase standards in research. Lead by four researchers – Marcus Munafò (Psychologist, University of Bristol), Laura Fortunato (Anthropologist, University of Oxford), Chris Chambers (Neuroscientist, University of Cardiff) and Malcolm Macleod (Neuroscientist, University of Edinburgh), the network is made up of a steering committee and two groups: Local Network Leads and Stakeholders.

The Local Network Leads are researchers, each representing a university. Together, they provide on-the-ground support within universities to help other researchers and policymakers navigate this complex area. UKRN wants local network leads to create excitement and buzz about doing high quality research. They support for example local ‘Reproducibilitea journal clubs’, where researchers collectively review research papers and discuss methodological issues.

The Stakeholders group is made up of representatives from research-related organisations, including Wellcome, UKRI, MRC, Nature, PLOS, JISC, UK Research Integrity Office, Universities UK and many more. Each organisation contributes small grants to UKRN, including Wellcome. By engaging these two key groups, UKRN aims to achieve both a bottom-up and top-down influence on UK research culture.

I attended the second half of the meeting, which was specifically for the Stakeholders. The focus of this meeting was the work plan for the year ahead. Discussion was lively, ranging from the responsibility of funders like Wellcome to those of journals such as Nature, data sharing and open access policies, the value of ‘metaresearch’ – or ‘research on research’ – and expanding discussions on these issues beyond biomedical science. The incentive structures within academia came up frequently as a key cause for concern. With publishing in a high-impact journal still seen as the key measure of success in science, despite intitives such as DORA, the concern is that pressure to publish could lead researchers to behave less than perfectly. As one attendee said, this is a “systemic issue, which needs a systemic solution”. That’s where UKRN’s strength lies. They have managed to get so many key stakeholders in a room at once to discuss these issues and commit to finding solutions that it feels like real change is on the horizon.

The potential of UKRN is exciting, and there is a sense that it is capitalising on a cultural moment in science right now; those involved feel there is a real appetite for change from a number of directions. But it’s important to remember it’s a very small organisation, with an administrator as the only paid member of staff – everybody else is involved on a purely voluntary basis. There’s only so much an organisation like that can achieve in a year. However the plans UKRN have set out for the next year are bold and ambitious: it will for example continue ongoing work (funded through the Wellcome Research on Research scheme) on linking the registered reports system with funding decisions; it will plan a large conference for next year, bringing together relevant parties for extended conversations and workshops; it will continue to grow its network and build an evidence base for improving research integrity.

So, watch this space – and the UKRN twitter account – as this network will only continue to grow and develop its influence over the coming year, with support from Wellcome and other funders.

Can cognitive interventions change our perception from negative to positive, and might that be useful in treating depression?

By Sarah Peters

Have you ever walked away from a social interaction feeling uncomfortable or anxious? Maybe you felt the person you were talking to disliked you, or perhaps they said something negative and it was all you could remember about the interaction. We all occasionally focus on the negative rather than the positive, and sometimes ruminate over a negative event, but a consistent tendency to perceive even ambiguous or neutral words, faces, and interactions as negative (a negative bias), may play a causal role in the onset and rate of relapse in depression.

A growing field of psychological interventions known as cognitive bias modification (CBM) propose that by modifying these negative biases it may be possible to intervene prior to the onset of depression, or prevent the risk of subsequent depressive episodes for individuals in remission. Given that worldwide access to proven psychological and pharmacological treatments for mood disorders is limited, and that in countries like the UK public treatment for depression is plagued by long waiting lists, high costs, side effects, and low overall response rates, there is a need for effective treatments which are inexpensive, and both quick and easy to deliver. We thought that CBM might hold promise here, so we ran a proof of principle trial for a newly developed CBM intervention that shifts the interpretation of faces from negative to positive (a demonstration version of the training procedure can be seen here). Proof of principle trials test an intervention in a non-patient sample, which is important to help us understand a technique’s potential prior to testing it in a clinical population – we need to have a good idea that an intervention is going to work before we give it to people seeking treatment!

In this study, we had two specific aims. Firstly, we aimed to replicate previous findings to confirm that this task could indeed shift the emotional interpretation of faces. Secondly, we were interested in whether this shift in interpretation would impact on clinically-relevant outcomes: a) self-reported mood symptoms, and b) a battery of mood-relevant cognitive tasks. Among these were self-report questionnaires of depressive and anxious symptoms, the interpretation of ambiguous scenarios, and an inventory of daily stressful events (e.g., did you “wait too long in a queue,” and “how much stress did this cause you on a scale of 0 to 7”). The cognitive tasks included a dot probe task to measure selective attention towards negative (versus neutral) emotional words, a motivation for rewards task which has been shown to measure anhedonia (the loss of pleasure in previously enjoyed activities), and a measure of stress-reactivity (whereby individuals complete a simple task under two conditions: safe and under stress). This final task was included because it is thought that the negative biases we were interested in modifying are more pronounced when an individual is under stress.

We collected all of our self-report and cognitive measures at baseline (prior to CBM), after which participants underwent eight sessions (in one week) of either CBM or a control version of the task (which does not shift emotional interpretation). We then collected all of our measures again (after CBM). In order to be as sure of our results as possible, there were a number of critical study design features we used. Our design, hypotheses, and statistical analyses were pre-registered online prior to collecting data (this meant that we couldn’t fish around in our data until we found something promising, then re-write our hypotheses to make that result seem stronger). We also powered our study to be able to detect an effect of our CBM procedure. This meant running a statistical calculation to ensure we had enough participants to be convinced by any significant findings, and their potential to be clinically useful. This told us we needed 104 individuals split evenly between groups. Finally, our study was randomised (participants were randomly allocated to the intervention group or the control group), controlled (one group underwent an identical “placebo” procedure), and double-blind (only an individual who played no role in recruitment or participant contact knew which group any one participant was in).

So, what did we actually find? While the intervention successfully shifted the interpretation of facial expressions (from negative to positive), there was only inconclusive evidence of improved mood and the CBM procedure failed to impact most measures. There was some evidence in our predicted direction that daily stressful events were perceived as less stressful by those in the intervention group post-CBM, and weaker evidence for decreased anhedonia in the intervention group. In an exploratory analysis, we also found some evidence that results in the stress-reactivity task were moderated by baseline anxiety scores – for this task, the effects of CBM were only seen in individuals who had higher baseline anxiety scores. However, exploratory findings like this need to be treated with caution.

Therefore, as is often the case in scientific research, our results were not entirely clear. However, there are a few limitations and directions for future research that might explain and help us to interpret our findings. Our proof of principle study only considered effects in healthy individuals. Although these individuals were clearly amenable to training, and may indeed have symptoms of depression or anxiety without a clinical diagnosis, our observation that more anxious individuals appeared to be more affected by the intervention warrants research in clinical populations. In fact, a reasonable parallel to the effects observed in this study may be working memory training, which does not transfer well to other cognitive operations in healthy samples, but shows promise as a tool for general cognitive improvement in impaired populations.

Future research is also needed to disambiguate the tentative self-report stress and cognitive anhedonia effects observed here. One possibility, for example, is that the 104 participants we recruited were not enough to detect an effect of transference from CBM training to other measures (the size of which is unknown). Given the complexity of any mechanism through which a computerised task could shift the perception of faces and then influence behaviour, it is likely that a larger sample is necessary. While it could be argued that if such a large group of individuals is warranted to detect an effect, that effect is likely too small to be clinically useful, we would argue that even tiny effects can indeed be meaningful (e.g., cancer intervention studies often identify very small effects which can have a meaningful impact at a population level).

Another explanation for our small effects is that while one week was long enough to induce a change in bias, it may not have been long enough to observe corresponding changes in mood. For instance, positive interpretation alone may not be enough – it may be that individuals need to go out into the world and use this new framework to have personal, positive experiences that gradually improve mood, and this process may take longer than one week.

Overall, this CBM procedure may have limited impact on clinically-relevant symptoms. However, the small effects observed still warrant future study in larger and clinical samples. Given the large impact and cost of mood disorders on the one hand, and the relatively low cost of providing CBM training on the other, clarifying whether even small effects exist is likely worthwhile. Even if this procedure fails to result in clinical improvement, documenting and understanding the different steps in going from basic scientific experimentation to intervening in clinical samples is crucial for both the scientific field and the general public to know. The current study is part of a body of research which should encourage all individuals who are directly or indirectly impacted by depression or other mood disorders. Novel approaches towards understanding, preventing, and treating these disorders are constantly being investigated, meaning that we can be hopeful for a reduction in the devastating impact they currently have in the not so distant future.

Read the published study here

Sarah Peters can be contacted via email at: s.peters@bristol.ac.uk

Supervised injectable heroin for refractory heroin addiction

by Eleanor Kennedy @Nelllor_

This blog originally appeared on the Mental Elf site on 28th August 2015.

Opioid use is the number one reason for seeking substance misuse treatment across 30 European countries. Opioids are drugs derived from the opium poppy and these include the drug heroin (EMCDDA, 2015).

Heroin dependence has negative consequences for both the individual and society as persistent use of the drug is associated with poor health, criminal offences and damaged personal relationships (Ferri et al, 2011). Drug-free treatments and substitution treatments are the two interventions used to overcome heroin dependence.

Methadone is the most common substitution treatment in the EU, however, heroin prescribing is well established in Denmark, Germany and The Netherlands, an option in the UK and Spain, and currently under investigation in Belgium and Luxembourg (EMCDDA, 2015).

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis aims to compare supervised injectable heroin (SIH) as a treatment for heroin users who have not responded to more standard treatments such as methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) or residential rehabilitation (Strang et al, 2015).

Methods

Electronic databases (PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus) were searched for studies that reported on the effects of SIH treatment in participants with heroin-dependence unresponsive to standard treatments.

The studies had to have opiate use, retention in treatment, mortality and side-effects as outcome variables.

Studies were excluded if they were methodological papers, assessed unsupervised heroin treatment provision, focused on policy aspects, cost effectiveness, community perspectives or patient satisfaction.

The meta-analysis focussed on Mantel-Haenszel random effects pooled risk ratios for SIH treatment compared to the comparison groups.

Results

There were a total of six papers included in the main review and meta-analysis. These studies were based in Switzerland, The Netherlands, Spain, Germany, Canada and England.

All studies explored SIH compared to MMT (oral methadone) in chronic heroin-dependent individuals who have repeatedly failed in orthodox treatment.

The results of rate of retention and the use of illicit heroin following treatment are shown in Table 1. The rates of retention varied across studies, with only one study reporting a lower rate of retention for the SIH group (Van den Brink et al, 2003). The statistical evidence indicated a lower rate of illicit heroin use in individuals receiving SIH treatment in all six studies.

Table 1: Retention in treatment and use of illicit heroin results

| Study | Retention in treatment | Use of illicit heroin |

| Perneger et al, 1998 | SIH 93% vs MMT 92% | p = 0.002 |

| Van den Brink et al, 2003 | SIH 72% vs MMT 85% | P = 0.002 |

| March et al, 2006 | SIH 74% vs MMT 68% | P = 0.02 |

| Haasen et al, 2007 | SIH 67% vs MMT 40% | P < 0.001 |

| Oviedo-Joekes et al, 2009 | SIH 88% vs MMT 54% | P = 0.004 |

| Strang et al, 2010 | SIH 88% vs MMT 69% | P < 0.0001 |

Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted to explore retention in treatment, mortality outcome and side-effects.

- Retention in treatment was significantly better for the SIH than for the MMT treatment groups as demonstrated by four studies; RR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.83

- Mortality was lower in the SIH than in the MMT treatment groups but this was not significant; RR=0.65, 95% CI = 0.25 to 1.69

- There was a higher risk of side effects in the SIH compared to the MMT treatment groups based on analysis of five studies; RR = 4.99, 95% CI = 1.66 to 14.99

Strengths and limitations

All of the included studies were randomised controlled trials comparing traditional oral MMT to SIH in participants with chronic heroin-dependence who have not been successfully treated. The review followed PRISMA guidelines and was inclusive of all languages and publication dates, so the likelihood of important papers being excluded is minimal.

In this review the authors focussed on supervised administration of heroin only, which contrasts with a 2011 Cochrane Review that also included studies where heroin was prescribed for take-home administration (Ferri et al, 2011). By restricting the inclusion criteria, stronger conclusions can be made about the efficacy of this type of treatment which may guide the introduction of new interventions. Additionally the authors’ address several key misgivings about SIH, which further supports the argument that SIH is an effective treatment for treatment-resistant heroin dependence. For example, the concern that SIH may undermine other existing treatments is countered by the difficulty in recruitment experienced by many of the six trials under review.

There are some limitations, e.g. the safety of injectable diamorphine requires further research as the instances of sudden-onset respiratory depression is at a rate of about 1 in 6,000 injections.

Conclusions

The authors concluded that:

Based on the evidence that has been accumulated through these clinical trials, heroin-prescribing, as a part of highly regulated regimen, is a feasible and effective treatment for a particularly difficult-to-treat group of heroin dependent patients.

The importance of supervision during administration is emphasised throughout the review. As mentioned above, all of the participants engaged in SIH had previously repeatedly failed in orthodox treatment, however, the evidence supports SIH as a treatment option for these individuals.

Links

Primary paper

Strang J, Groshkova T, Uchtenhagen A. et al. (2015) Heroin on trial: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials of diamorphine-prescribing as treatment for refractory heroin addiction. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015;207:5-14. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.149195.

Other references

EMCDDA (2015) European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. emcdda.europa.eu. 2015. Available at: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu

Ferri M, Davoli M, Perucci CA. Heroin Maintenance for chronic heroin-dependent Individuals. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 12. Art. No .: CD003410. DOI: 10.1002 / 14651858.CD003410.pub4.

Van den Brink W, Hendriks VM, Blanken P, Koeter MWJ, van Zwieten BJ, van Ree JM. (2003) Medical prescription of heroin to treatment resistant heroin addicts: two randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2003;327(August):310. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7410.310.

Perneger T V, Giner F, del Rio M, Mino A. (1998) Randomised trial of heroin maintenance programme for addicts who fail in conventional drug treatments. BMJ 1998;317(July):13-18. doi:10.1136/bmj.317.7150.13.

March JC, Oviedo-Joekes E, Perea-Milla E, Carrasco F. (2006) Controlled trial of prescribed heroin in the treatment of opioid addiction. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2006;31:203-211. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2006.04.007. [PubMed abstract]

Haasen C, Verthein U, Degkwitz P, Berger J, Krausz M, Naber D. (2007) Heroin-assisted treatment for opioid dependence: Randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007;191:55-62. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.026112.

Oviedo-Joekes E, Brissette S, Marsh DC, et al. (2009) Diacetylmorphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:777-786. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810635. [Abstract]

Strang J, Metrebian N, Lintzeris N, et al. (2010) Supervised injectable heroin or injectable methadone versus optimised oral methadone as treatment for chronic heroin addicts in England after persistent failure in orthodox treatment (RIOTT): a randomised trial. Lancet 2010;375(9729):1885-1895. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60349-2. [Abstract] [Watch Prof John Strang talk about the RIOTT trial]

– See more at: http://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/substance-misuse/supervised-injectable-heroin-for-refractory-heroin-addiction/#sthash.hvYELhgt.dpuf

Are changes in routine health behaviours the missing link between bereavement and poor physical and mental health?

by Olivia Maynard @OliviaMaynard17

This blog originally appeared on the Mental Elf site on 6th July 2015.

While bereavement can occur at any point during the lifespan, it is much more common later in life and is a risk factor for both poor physical and mental health.

While the Mental Elf has blogged previously about the impact of childhood bereavement on mental health, the impact of bereavement on the health of older people can be even more severe, given the ongoing declines in health as a result of their age.

Due to the high prevalence of bereavement in this age group, understanding how bereavement leads to declines in health among older adults is important. Behavioural changes may partially account for these negative health outcomes.

To examine this, Stahl and Schulz (2014) conducted the first systematic review to examine the relationship between bereavement and five routine health behaviours:

- Physical activity

- Nutrition

- Sleep

- Alcohol use

- Tobacco use

As well as one modifiable risk factor associated with health:

- Body weight

Methods

The authors searched databases to find 34 studies which met the following criteria:

- Quantitative and qualitative studies with either observational or intervention-based designs;

- Older adults (aged over 50 years) who had experienced the death of a spouse;

- Health behaviours were assessed.

Results

Physical activity

18 studies: 4 cross-sectional, 8 prospective longitudinal, 5 post-bereavement longitudinal

- Physical activity was assessed using self-report in all studies and physical activity ranged from social activities such as visiting friends to sports activities.

- As a result, the evidence was mixed, with bereavement increasing the prevalence of social activities, but decreasing the prevalence of sports. Furthermore, while this pattern applied to bereaved women, bereavement decreased all forms of physical activity among men.

Nutrition

12 studies: 5 cross-sectional, 5 prospective longitudinal, 3 post bereavement longitudinal

- Nutrition was assessed using a range of self-report questionnaires.

- There was consistent evidence for a strong relationship between bereavement and increased nutritional risk, including worse nutrient intake and poor dietary behaviours, particularly within the first year of bereavement.

Sleep quality

9 studies: 1 cross-sectional, 0 prospective longitudinal, 8 post-bereavement longitudinal

- Sleep quality was assessed using both self-report and objective measures such as electroencephalography and actigraphy (measurement of movement using small body sensors).

- While the self-report studies consistently showed strong support for a link between bereavement and poorer sleep quality, no relationship was observed when sleep disturbance was measured objectively.

Alcohol consumption

7 studies: 2 cross-sectional, 3 prospective longitudinal, 2 post-bereavement longitudinal

- There was moderate evidence (from longitudinal studies only) that bereavement was associated with increased self-reported alcohol consumption, for both men and women.

Tobacco use

7 studies: 2 cross-sectional, 4 prospective longitudinal, 1 post-bereavement longitudinal

- Smoking status and frequency of tobacco use was assessed using self-report.

- There was inconsistent evidence for the impact of bereavement on smoking behaviour, with bereavement reducing smoking frequency among current smokers (particularly men) but increasing the likelihood of smoking initiation among female non-smokers.

Weight status

6 studies: 1 cross-sectional, 5 prospective longitudinal, 0 post-bereavement longitudinal

- There was consistent evidence across the studies that bereavement led to unintentional weight loss among both men and women.

Limitations and directions for future research

- The studies were heterogeneous and many did not report effect sizes, meaning that quantitatively assessing them (i.e. using meta-analysis) was not possible.

- The majority of studies used self-report which may be affected by recall bias. For studies exploring sleep quality, only those which used self-report, rather than objective measures observed a negative effect of bereavement.

- Few of the longitudinal studies reported the length of the bereavement period or when assessments were taken. Precise information on measurement intervals is important in determining when behavioural changes are most likely to occur and would be important for treatment.

Discussion

This systematic review observed:

- Strong support for changes in nutrition, sleep quality and weight status after bereavement

- Moderate evidence for an impact on alcohol consumption

- Mixed evidence for effects on physical activity and tobacco use

Although this review did not explore why bereavement led to these changes in health behaviours, the authors provide a number of explanations, which should be examined in future studies:

- Loss of social support and the onset of depression and grief. This may reduce motivation to engage in health-promoting behaviours such as physical activity and also exacerbate or trigger physical symptoms such as poor sleep and headaches.

- Changes in daily routines. Previously shared activities, such as exercise, food preparation or sleeping, may be difficult to maintain following spousal loss.

Crucially, however, this review is only one part of the puzzle. While it shows us that bereavement is associated with changes in health behaviours, we don’t know whether these changes mediate the relationship between bereavement and physical and mental health, the key outcome we’re interested in.

Given the known health burden associated with bereavement, it is critical that we further investigate this link and if this link were observed, interventions could target health behaviours to reduce the impact of bereavement on physical and mental health.

Links

Primary paper

Stahl ST, Schulz R. (2014) Changes in routine health behaviors following late-life bereavement: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37, 736-755.

– See more at: http://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/are-changes-in-routine-health-behaviours-the-missing-link-between-bereavement-and-poor-physical-and-mental-health/#sthash.QRsZgV2E.dpuf

Financial incentives for smoking cessation in pregnancy

By Meg Fluharty @MegEliz_

This blog originally appeared on the Mental Elf site on 11th March 2015.

Smoking during pregnancy is thought to cause approximately 25,000 miscarriages per year in the United Kingdom (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2010).

Additionally, smoking while pregnant is attributable to 4-7% of stillbirths (Flenady et al., 2011), and 3-5% of infant deaths (Gray et al., 2009) with these rates even higher in deprived areas, where remaining a smoker during pregnancy is more common (Gray et al., 2009).

In 2009, 24% of women attending antenatal appointments in Scotland were smokers (NHS, 2009). However only 1 in 10 reported using cessation services, and 3% were abstaining by four weeks (Tappin et al., 2010).

A recent Cochrane systematic review suggested financial incentives may be beneficial in helping pregnant women stop smoking, although it concluded that further evidence was needed (Chamberlain et al., 2013). Tappin et al (2015) investigated the effectiveness of shopping vouchers in addition to NHS Stop Smoking Services to aid quit attempts in pregnant women.

Methods

The authors conducted a randomised controlled trial of 609 pregnant smokers recruited from NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. Women were randomly allocated to routine smoking cessation care (control group) or to routine care and up to £400 in shopping vouchers if they engaged with services and successfully quit smoking (incentives group).

Routine care

Routine specialist pregnancy care involved an initial meeting to discuss quitting smoking and set a quit date. This was followed by 4 weekly telephone calls, and free nicotine replacement therapy for 10 weeks.

Incentives group

The incentives group received £50 in shopping vouchers for attending the initial meeting to set a quit date. If participants were smoke-free 4 weeks later, they would receive another £50 voucher, and if smoke-free at 12 weeks, participants received £100 in gift vouchers. Between 34-38 weeks gestation, women were once again asked smoking status, and those who had quit received a final £200 voucher. In all instances, smoking status was verified by a carbon monoxide breath test.

Results

- More women successfully quit smoking in the incentives group (22.5%) than the routine care group (8.6%).

- There was a higher quit rate at 4 weeks in the incentives group compared to the routine care group.

- 12 months after quit date, there was still large difference in self-reported quit rates (15% incentives, 4% control).

- Women lost to follow-up were assumed to be smokers, which was validated by analysing residual routine blood samples for cotinine.

Summary

This study demonstrated that financial incentives with routine care could be beneficial in motivating quit attempts in pregnant smokers, as well as aiding them in continuing to abstain up to 12 months after their quit date. Furthermore, the quit rates reported in this trial were larger than many pharmaceutical (Coleman et al., 2012) or behavioural (Chamberlain et al., 2013) intervention trials in pregnant women. Although, it should be noted that women in the control group had higher nicotine addiction scores than those in the incentives group.

While the evidence from this study suggests using financial incentives may be beneficial in helping pregnant smokers to stop, there may be practical and ethical issues in implementing this as an intervention.

Additionally, other studies are needed to determine the generalizability and possible cost effectiveness of this intervention, as well as what cessation services are best suited to pair with financial incentives. However, it will be interesting to see how this study may be used to inform future policy.

Links

Tappin D, Bauld L, Purves D, Boyd K, Sinclair L, MacAskill S et al. Financial incentives for smoking cessation in pregnancy: randomised controlled trial (pdf). BMJ 2015; 350:h134

Health and Social Care Information Centre, Infant feeding survey 2010 (pdf). HSCIC, 2012. www.hscic.gov.uk/pubs/ifs2005.

Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, Frøen JF, Smith GC, Gibbons K, et al. Major risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011;377:1331-40. [Abstract]

Gray R, Bonellie SR, Chalmers J, Greer I, Jarvis S, Kurinczuk J, et al. Contribution of smoking during pregnancy to inequalities in stillbirth and infant death in Scotland 1994-2003: retrospective population based study using hospital maternity records. BMJ 2009;339:b3754.

Information Services Division, NHS National Services Scotland. Births and babies: smoking and pregnancy, 2009. www.isdscotland.org/isd/2911.html.

Tappin DM, MacAskill S, Bauld L, Eadie D, Shipton D, Galbraith L. Smoking prevalence and smoking cessation services for pregnant women in Scotland. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2010;5:1.

Coleman T, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, Cooper SE, Leonardi-Bee J. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9:CD010078. [Abstract]

Chamberlain C, O’Mara-Eves A, Oliver S, Caird JR, Perlen SM, Eades SJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;10:CD001055

– See more at: http://www.thementalelf.net/mental-health-conditions/substance-misuse/financial-incentives-for-smoking-cessation-in-pregnancy/#sthash.upeNCXSE.dpuf

Welcome to the TARG blog

Hi there everyone!

I’m Suzi Gage, a PhD student in TARG, and an avid blogger. I have a science blog called Sifting the Evidence, which is on the Guardian website. I love writing about science, for a variety of reasons. I believe that since most research conducted in Universities is carried out using money which has ultimately come from the public, we as researchers have a duty to share any results we find. This can be hard due to journals sometimes having paywalls, meaning research isn’t freely available. Also, academic papers are often written in dry technical language which can be confusing or boring to read.

Blogging is a great way of sharing our findings with those people who are interested in what we get up to. We intend to use this TARG blog to do just this, as well as writing posts more generally about the type of research we do, or background summaries of areas of research we are interested in.

If there’s anything you’d like us to cover, do let us know.

A first post will be up soon. Enjoy!