Written by Angela Attwood and Olivia Maynard, with reflections from Marcus Munafò

Beyond the immediate impact on people’s lives and livelihoods, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has caused a great deal of disruption in how we work. The burden on academics, particularly with respect to teaching, has been considerable. But are there positives that we can take from this situation?

Academia can be surprisingly conservative – we have ways of working that we are reluctant to change. While undergraduate courses may have been tweaked in response to student feedback, they remain largely unchanged from the courses available in the 1990s. Yet over this same period the ways that young people digest knowledge has changed radically. Today’s undergraduates are digital natives, used to receiving content in very different (and more flexible) ways.

Once we knew the pandemic would force us to move to online teaching, and that we’d be delivering our third-year optional psychology unit on ‘Drug Use and Addiction’ online, we knew we had to take the opportunity to completely overhaul our course and update our pedagogy.

We started by identifying key principles that would inform the redesign of the course. As we outline below, we aimed to: ensure clarity, maximise engagement, facilitate presence, tackle the “valuable but missable” problem of live sessions, and be flexible.

Our redesigned course followed a flipped lecture format, whereby asynchronous material was delivered ahead of an online live (synchronous) session. This flipped approach is known to have pedagogical benefits over traditional didactic lectures. This was a substantial structural change to our course, but throughout we tried to avoid reinventing the wheel! Rather we wanted to create a course that was pedagogically sound, based on current evidence, and shaped by our key principles.

The feedback so far from students has been overwhelmingly positive (perhaps even more so than in previous years!) and we strongly believe our principles have been key to the success of the course. We therefore want to expand on each principle and share what we have learned so far, in case this is helpful for others also faced with the daunting task of complete course redesign.

Principle 1: Ensuring clarity

More than anything else, it was essential that students understood what they needed to do and why they need to do it.

What we did:

- Created a consistent structure. We had folders for each sub-unit (previously lectures, but “sub-unit” better captures the granular nature of the content). Released weekly, these contained all teaching material (e.g., pre-recorded mini “lectures”, reading, etc.) for that week.

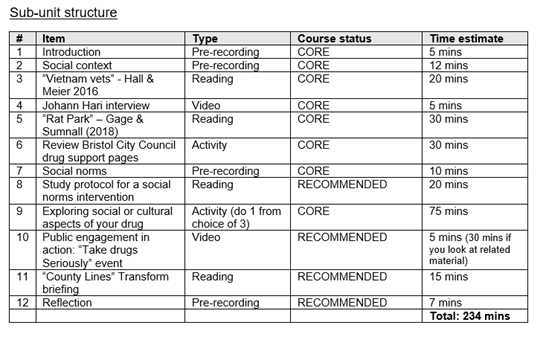

- Ensured requirements were clear. Each sub-unit started with a “roadmap”, including a summary of the sub-unit, intended learning outcomes, and an ordered list of tasks for completion, with an estimate of the time required for each.

- Clarified the importance of each task. We labelled these as either as CORE or RECOMMENDED. This allowed students flexibility, as they could choose to leave or return to RECOMMENDED items.

- Provided guidance notes for all academic reading (i.e., journal articles, book chapters). This included an overview (why it was chosen), any focussed reading (particularly useful for long review articles), and key “take home” messages *.

* This was an unexpected “win” as our discussion board inbox was significantly quieter this year. Many questions in previous years asked how to make notes on or read journal articles in the context of the course. The number of these questions received at the point of writing is zero!

Example sub-unit structure from one of the “roadmaps”

Student feedback

“The structure for the sub-units is SO helpful, really like how it tells you how much time each activity is going to take.”

“The pre-recordings are a very good length, and the little summary of everything we are doing for the sub-unit with the timings is incredibly helpful.”

Principle 2: Maximising engagement

Students are spending more time working at home, due to local or national restrictions, or limits on campus study space. This means that as well as material needing to be high quality, it also needs to be interesting and engaging. We focussed on material that was digestible, offered various methods of delivery, and gave students flexibility in how they structured their own learning.

What we did:

- Lectures recorded into bitesize chunks (ideally of no more than 20 minutes each). This reduced the burden associated with listening to each lecture and provided students with more flexibility when it came to organising their learning.

- Academic reading was supplemented with additional materials (e.g., videos, podcasts, websites). This allowed students to explore areas of personal interest more deeply if they wished to.

- Student-led activities (e.g., interview their friends, own literature searches, evaluate websites, mini-experiments). This provided opportunities for students to again explore areas of personal interest more deeply, in a range of different ways.

- Student choice (e.g., choosing a drug they were interested in, and activities that could be aligned to build a “portfolio” of materials specific to their drug of choice). This fed through to assessment where they could answer the question on any drug they wanted.

Student feedback

“I really like the sub-unit structure. As someone who doesn’t learn best unless there is a range of different learning stimuli in combination (e.g., lecture content, reading, visual cues like videos/stats graphs etc.) I find the subunits are so interesting and they help me to focus my energy onto the task at hand and stops me getting distracted.”

“I really enjoyed the variety and the fact it wasn’t just hours and hours of straight lectures which can get really dull! :)”

Principle 3: Facilitating presence

Working through material posted on a website can be isolating. It’s important to create a sense of community in online settings.

What we did:

- Used software that enabled student interaction and reflection throughout the week (e.g., Padlet, Mentimeter). We made sure at least one of these was present in each sub-unit, and encouraged students to communicate with each other as well as ourselves.

- Recorded “reflection” lectures between ourselves (lecturers) or invited guests. This ensured that students saw our faces during the week, as well as a range of different contributions from the wider academic community.

- Held weekly live sessions on Zoom to reflect on the week’s teaching. Although not strictly necessary, we both attended all live sessions to maximise our interaction with the students, and encouraged students to have their webcams on during these sessions (about half did).

- Held weekly live drop-in sessions (in addition to core live sessions) to answer questions and chat. This provided further opportunities to interact directly with ourselves and other students in real time.

- Used Zoom functions in live sessions – including breakout rooms – to give students a chance to talk to each other. We also used Zoom polling to ensure that all students had an opportunity to contribute, even if they didn’t feel like talking.

- Emailed the cohort regularly with additional opportunities, talks etc. relevant to the course. This created a sense of the wider academic community that they are part of, and the ongoing research activity relevant to the course.

Student feedback

“I really enjoyed the smaller rooms when on Zoom to talk to others in small groups of 5. Found it a lot easier to talk in these smaller groups than larger ones. I also liked the multiple-choice questions that you can present on the screen to see how everyone else is doing in terms of the sub units and the current work.”

Principle 4: Tackling the “valuable but missable” problem for live sessions

One of the biggest risks to any live session are technical issues. This created a “valuable but missable” paradox – we didn’t want to deliver core material during live sessions (so they could be missable if a student had Internet issues), but the sessions also had to be seen as valuable (or students might not attend!)

What we did:

- Constructed live sessions to be “skill building” (e.g., essay planning, argument building, debating skills, evidence synthesis and critique). These were designed to be valuable across the course as a whole, but any one could be missed with limited impact on assessment.

- Created different formats for the live sessions to make sure these were seen as valuable, but also interesting and engaging (e.g., discussion on how to answer a mock essay question, multiple choice quiz, hot topic debates).

Student feedback

“I really liked the quiz session last time, it made me think about the information I absorbed in the subunits, but equally I loved the debate. Practice essay questions are also very useful because I am struggling with planning my essays in general.”

“I think the live sessions have been very beneficial in a number of ways related to our essays, overall course understanding and guiding areas for reading.”

Principle 5: Being flexible (we are learning too!)

Co-design with end-users is vital for the best end-product. We allowed time to ask for student feedback, and space to respond to it.

What we did:

- Created polls that allowed students to vote on upcoming content (e.g., what question would be discussed in live sessions; what format of live sessions they find most helpful).

- Kept aspects of the course only partially developed (e.g., live session format) so that we had scope to be responsive to feedback.

- Continually asked for student feedback, via short polls and surveys on specific questions (e.g. ‘What should the format of the live sessions be?’, ‘How long should we stay in breakout groups for’) as well as asking for stop-start-continue feedback on the course as a whole, via an online survey that students could complete at any point during the course.

So, what does the future hold?

While we all hope ‘normal’ life will resume soon, the reality is that the world will not be quite the same post-pandemic. Much like many businesses that are planning to retain positive elements of home working, we should be open to retaining elements of our new ways of teaching. The crisis of the pandemic has created an opportunity to fundamentally overhaul and modernise the way that we teach that would have been unthinkable in a ‘normal’ year. And it seems to have worked – to quote a student, “It’s better than face to face teaching” (emphasis added).

We agree that these new ways of teaching are better – not just for students but for academics too. The recorded asynchronous material will stay current for 2 or 3 years (and perhaps longer for more introductory courses), meaning that if we retain this overall structure, our workload will be less next year. At the same time, many of the various synchronous elements can return to a face-to-face format, ensuring we spend more time in small groups, doing interactive work which both students and academics (certainly ourselves) find more engaging and fulfilling.

While our model is certainly not perfect – it had to be developed rapidly under considerable pressure – it’s a start, and offers a glimpse of the future.

Towards the end of last year headlines emerged about captagon, a psychoactive drug “

Towards the end of last year headlines emerged about captagon, a psychoactive drug “ The drug the media are calling captagon

The drug the media are calling captagon  But it is the more long-term, indirect consequences of a sensationalist media discourse that are probably the more harmful ones. The reinforcement of the notion that illegal drugs are one of the main

But it is the more long-term, indirect consequences of a sensationalist media discourse that are probably the more harmful ones. The reinforcement of the notion that illegal drugs are one of the main