by Olivia Maynard @OliviaMaynard17

This blog originally appeared on the Mental Elf site on 9th Febraury 2016.

Last month the UK Chief Medical Officers (CMOs) published new guidelines for alcohol consumption. These are the first new guidelines since 1995 and are based on the latest evidence on the effects of alcohol consumption on health.

The guidelines provide recommendations for weekly drinking limits, single drinking episodes and recommendations for pregnant women, drawing heavily on the Sheffield Alcohol Policy Model, which uses the most up to date evidence on both the short- and long-term risks of alcohol.

What are the new guidelines?

Guidelines for weekly drinking

For the new weekly drinking guidelines, the CMOs recommend that:

- It’s safest for both men and women to not regularly drink more than 14 units of alcohol per week;

- It’s best to spread these units over 3 days or more;

- Having several drink-free days each week is a good way of cutting down the amount you drink;

- The risk of developing a range of illnesses increases with any amount you drink on a regular basis.

There are two key changes here from the guidelines we’ve been used to:

First, there’s no difference in recommendations for men and women. This is because there is increasing evidence that although women are more at risk from the long-term health effects of alcohol, men are more at risk from the short-term effects of drinking (they’re more likely to expose themselves to risky situations while drinking).

Second, there is an explicit statement that there is no ‘safe’ level of alcohol consumption. Over the past 21 years, the link between alcohol and cancer has become much clearer. For example, we now know that while the lifetime risk ofbreast cancer is 11% among female non-drinkers, the lifetime risk for a woman drinking within the new guidelines is 13%. A woman drinking over 35 units a week increases her risk of breast cancer to 21%.

In their report, the CMOs are also at pains to point out that the evidence supporting alcohol’s protective effects on ischaemic heart disease is now weaker than in 1995. Furthermore, any potential protective effect of alcohol is mainly observed among older women at very low levels of consumption. Previously some have used this to claim that drinking is better than abstinence – the new guidelines refute this.

The new guidance says it’s safest for men and women to drink no more than 14 units each week.

Guidelines for single drinking episodes

The new guidelines are the first to provide guidance on drinking on single occasions, recommending drinkers:

- Limit the total amount consumed on any occasion;

- Drink slowly, with food and alternating with water;

- Avoid risky places and activities and ensure they have a safe method of getting home.

These new recommendations reflect the fact that many alcohol consumers may drink heavily on occasion and provide guidance to avoid the risk of injury and ischaemic heart disease which increase with heavy drinking.

Heavy drinking episodes are linked with a higher risk of injury.

Guidelines for drinking during pregnancy

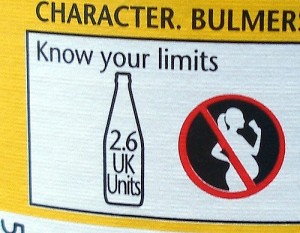

The new guidelines suggest that:

- The safest approach for pregnant women is not to drink alcohol at all, to keep risks to the baby to a minimum.

- Drinking during pregnancy can lead to long-term harm to the baby, with the risk increasing with the more alcohol consumed;

- The risk of harm to the baby is likely to be low if a woman has drunk only small amounts of alcohol before she knew she was pregnant or during pregnancy.

The CMOs report that while the evidence on the effects of low alcohol consumption during pregnancy remains ‘elusive’, taking a precautionary approach is most prudent when it comes to a baby’s long term health. However, given the elusive evidence, the guidance is also careful to note that mothers should not be too concerned if they have drunk early in their pregnancy, as this kind of stress may be even more harmful to the developing baby.

Pregnant women are advised not to drink alcohol at all.

A note on risk

These recommendations are based on a level of alcohol consumption which confers a 1% lifetime risk of death from alcohol. Their purpose is therefore tominimise risk from alcohol, rather than eliminate it. Indeed, the guidelines explicitly state that there is no safe level of alcohol consumption. So what does a 1% lifetime risk mean and how does this compare to other health behaviours?

Lifetime mean risks

- Being killed through BASE jumping (0.3%);

- Being killed in a car accident (0.4%);

- Being diagnosed with bowel cancer from eating three rashers of bacon every day (1%);

- Dying from an alcohol related disease, if drinking within the new guidelines (1%);

- Smokers dying from a smoking related disease (50%, although new estimates suggest that this may be as high as 67%).

Put in the context of smoking, the risk posed by drinking within the new guidelines seems tiny (although it’s still more risky than BASE jumping!) However, it’s important to note that alcohol consumption and smoking are quite different. Alcohol consumption is perceived as normal in our society and is much more prevalent than cigarette smoking. By contrast, the acceptability of smoking is reducing and unlike social alcohol consumers, smokers are constantly being told to quit smoking.

This 1% risk level is that which is deemed ‘acceptable’ by the CMO. However, everyone will have a different ‘acceptable’ level of risk, which depends in part on how much pleasure is obtained from drinking. While some will think that increasing their risk of death from alcohol to 5% is acceptable, others will not accept any risk and will use these guidelines to cut out alcohol completely.

Criticisms of the new guidelines

As expected, the ‘nanny state’ criticism has been bandied around in pubs, on message boards and on social media since the publication of these guidelines. Others claim that these new guidelines are simply scaremongering. However, it’s important to remember that these are recommendations, not rules.

The last word must go to CMO Professor Dame Sally Davies, who addressed this criticism by saying that:

What we are aiming to do with these guidelines is give the public the latest and most up- to-date scientific information so that they can make informed decisions about their own drinking and the level of risk they are prepared to take.

What do you think? Are these new guidelines useful? Will they help reduce alcohol related harm?

Links

Primary paper

Department of Health (2016) Health risks from alcohol: new guidelines. Open Consultation, 8 Jan 2016 (Consultation closes on 1 April 2016)

Department of Health (2016). Alcohol Guidelines Review – Report from the Guidelines development group to the UK Chief Medical Officers.

Other references

Centre for Public Health (2016). CMO Alcohol Guidelines Review – A summary of the evidence of the health and social impacts of alcohol consumption. Liverpool John Moores University.

Centre for Public Health (2016). CMO Alcohol Guidelines Review – Mapping systematic review level evidence. Liverpool John Moores University.

Department of Health (1995). Sensible drinking: Report of an inter-departmental working group.

Photo credits

Towards the end of last year headlines emerged about captagon, a psychoactive drug “

Towards the end of last year headlines emerged about captagon, a psychoactive drug “ The drug the media are calling captagon

The drug the media are calling captagon  But it is the more long-term, indirect consequences of a sensationalist media discourse that are probably the more harmful ones. The reinforcement of the notion that illegal drugs are one of the main

But it is the more long-term, indirect consequences of a sensationalist media discourse that are probably the more harmful ones. The reinforcement of the notion that illegal drugs are one of the main

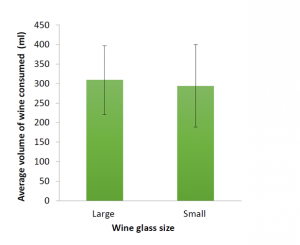

smaller glasses. As this study wasn’t powered to detect a meaningful difference between the two groups, we weren’t really surprised by this finding. However, these pilot data, along with the lessons learned from conducting the study will be used to inform our future research studies and grant applications.

smaller glasses. As this study wasn’t powered to detect a meaningful difference between the two groups, we weren’t really surprised by this finding. However, these pilot data, along with the lessons learned from conducting the study will be used to inform our future research studies and grant applications.