Katherine S. Button @ButtonKate

As if I don’t suffer enough with procrastination, I was recently sent an online Principal Investigator predictor tool, and encouraged to try it. This uses gender and publications to rank an individual against PIs and non-PIs, to calculate the likelihood that the individual will become a PI. This is based on a recent article which suggested that factors like number of first-author publications, and the Impact Factors of the corresponding journal, strongly predict the likelihood of becoming a PI. The fact that these things predict success isn’t surprising, although it’s perhaps a shame that success is so closely tied to such imperfect measures. Nevertheless, the tool helps you to reflect on whether you should focus effort on having more first-author publications, rather than those where your contribution might be lost in the crowd.

Initial scoffs about navel-gazing aside, I entered the PMIDs of my publications and was bemused (and chuffed!) to be told I had a 99% chance of becoming PI. Ever the cautious scientist, however, I was concerned my probability might be inflated by the several letters to editors that were the aftermath of a high-profile paper published in Nature Reviews Neuroscience. Thus the sensitivity analyses began…

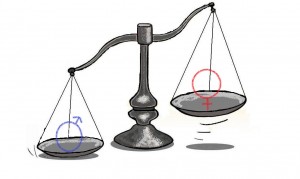

First I removed all letters and commentaries, restricting my publications to original research articles only, resulting in P(PI) = 81%. Not bad, but I was still concerned that the results were skewed by my one high-profile outlier. So I re-ran the prediction using only those publications which were completely independent of the NRN paper, resulting in P(PI) = 73%. Less good. Then, out of feminist curiosity, I ran the same prediction but this time stating that I was male, resulting in P(PI | Male) = 82%. So, changing my sex from female to male had the same effect as a first author publication in Nature Reviews Neuroscience. Damn.

Dismayed, but not surprised, I then re-ran the other analyses for my male alter-ego. The effects were less dramatic for the original research articles, P(PI | male) = 88%, corresponding to a 7% advantage for being male, and had no effect when I used all my publications, P(PI | male) = 99%. This suggests that the probability of making it as a PI decreases with decreasing research outputs at a disproportionately higher rate for women than men.

Science has never been so competitive, and it’s difficult to successfully make the transition to independent scientist unless you’re a high-flier. An argument often levelled at women is that they are too risk averse to make it in such a competitive environment. But it seems to me that, rather than being risk averse, pursuing an independent career may simply be more risky for women who, given the same objective level of ability as a man, are less likely to succeed to PI.

This fits with my pet theory that sex biases in academia are most influential at the mid-range of ability. The brilliant high-fliers will probably succeed regardless of their sex. It’s at the mid-range where men may have an advantage compared with women of the same quality, who are disproportionality penalised.

I think role models are important in encouraging women to stay in STEM subjects. We need to see that other women have succeeded but also that the cost of success is reasonable; not everyone wants to devote every waking minute to science, and those that do (male or female) will no doubt already be well on their way to international stardom. For the rest of us, we want to have a scientifically valuable and worthwhile career and a reasonable family and social life. If this balance comes at the cost of being a talented but “average” scientist, then so be it, but why should such a choice disproportionality penalise women?

After a glib Tweet suggesting I might consider a sex change if my publications drop off, I was pointed in the direction of a Nature article Does Gender Matter written by Ben Barres, a man who has experienced working in science as both genders. The article is excellent, tackling the “women are innately less good than men” argument with a critical look at the evidence. Sticking with the anecdotal for now, however:

“Shortly after [Ben Barres], changed sex, a faculty member was heard to say “Ben Barres gave a great seminar today, but then his work is much better than his sister’s.”

Unfortunately this resonates all too well with discussions I’ve had with colleagues about the high rate of attrition of women in science who have suggested that men at the post-doctoral level are simply stronger candidates. These implicit beliefs about the superior competency of men over women, which are unfounded in terms of objective evidence, are no doubt at the heart of why proportionally fewer women succeed in science. Outstanding female scientists may suffer less from such biases, because the fact that they are outstanding makes them noteworthy. But the majority of scientists (both male and female) are worthy and talented but not outstanding, and here women may suffer disproportionately compared to their male counterparts.

As a psychologist studying how implicit cognitions bias behaviour, I’m in favour of positive discrimination to re-dress the balance. We have clear evidence that implicit sex discrimination pervades all aspects of the scientific process (on the part of both men and women). One often hears the counter-argument no female scientist wants to be appointed as a token gesture to address gender imbalance in a science department, or that all appointments should be on merit alone. But not all scientists can be world leaders, and the vast majority of PIs are talented but (by definition) average.

So, where gender bias is extreme (as I suspect it is in many science departments), let’s have judicious use of positive discrimination in the short-term. What’s the worst that can happen? You might appoint a talented but “average” woman, but she’s likely to be no less talented than an average male counterpart, and at least there’ll be more role models for us women who value our work-life balance.