By David Troy @DavidTroy79

I recently hosted a documentary screening of ‘A Royal Hangover’ on behalf of the Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group at the University of Bristol. The film documents anecdotes from all facets of the drinking cultur e in the UK, from politicians to police, medical specialists to charities, the church and scientists, and addicts and celebrities, with high profile personalities such as Russell Brand and controversial figures such as sacked Government Drugs Advisor Professor David Nutt. The director Arthur Cauty kindly agreed to take part in a question and answer session after the film to discuss his experience making the film and debate the issues raised in the film.

e in the UK, from politicians to police, medical specialists to charities, the church and scientists, and addicts and celebrities, with high profile personalities such as Russell Brand and controversial figures such as sacked Government Drugs Advisor Professor David Nutt. The director Arthur Cauty kindly agreed to take part in a question and answer session after the film to discuss his experience making the film and debate the issues raised in the film.

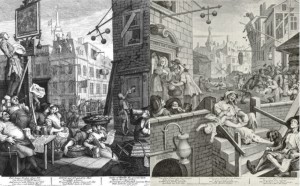

The film begins with Arthur talking about his own relationship with alcohol (or his lack of one). He preferred to shoot silly films, play music or wrestle than go out drinking with his friends. The film deals with the history of alcohol starting off in the 16th and 17th century when it was safer to drink beer than water. Even babies were given what was called “small beer for small people”. In the early 18th century, gin became the drink of choice and reached epidemic levels, famously depicted in William Hogarth’s ‘Gin Lane’.  Gin was unregulated and sold not just in public houses but in general stores and on the street. Moving on to the 20th century, Lloyd George recognised the danger of alcohol to the war effort in World War 1, and was quoted as saying that “we are fighting Germany, Austria and drink; and as far as I can see, the greatest of these deadly foes is drink”. Around this time, restrictions on the sale of alcohol were introduced by government. During World War 2, beer was seen as important to morale and a steady supply of it was seen as important to the war effort. Since then, we have seen a steady increase in consumption levels through the ‘hooligan/lager lout’ phenomenon of the 1980’s and the binge drinking of the 1990’s and the early 2000’s. Consumption levels have been falling slightly since the mid 2000’s but there are still 10 million people drinking above the government’s recommended level.

Gin was unregulated and sold not just in public houses but in general stores and on the street. Moving on to the 20th century, Lloyd George recognised the danger of alcohol to the war effort in World War 1, and was quoted as saying that “we are fighting Germany, Austria and drink; and as far as I can see, the greatest of these deadly foes is drink”. Around this time, restrictions on the sale of alcohol were introduced by government. During World War 2, beer was seen as important to morale and a steady supply of it was seen as important to the war effort. Since then, we have seen a steady increase in consumption levels through the ‘hooligan/lager lout’ phenomenon of the 1980’s and the binge drinking of the 1990’s and the early 2000’s. Consumption levels have been falling slightly since the mid 2000’s but there are still 10 million people drinking above the government’s recommended level.

During the film, Arthur investigates how different societies treat alcohol. French and American drinkers describe a more reserved and responsible attitude to alcohol. This is somewhat contradicted by 2010 data in a recent report by the World Health Organisation which reports that French people over the age of 15 on average consume 12.2 litres of pure alcohol a year compared to Britons at 11.6 and Americans at 9.2 litres respectively. The drinking culture of France and the United States is certainly different to that of the UK. The French consume more wine, less beer, and tend to drink alcohol whilst eating food. The US (outside of ‘Spring Break’ culture) is more disapproving of public intoxication. However, neither society should be held up as a gold standard when it comes to alcohol use.

The film talks about the enormous cost of alcohol to England; approximately £21 billion annually in healthcare (£3.5 billion), crime (£11 billion) and lost productivity (£7.3 billion) costs. These are the best data available, but costs of this nature are difficult to calculate. Arthur talked to professionals on the front line – he interviewed a GP who said that a huge proportion of her time is devoted to patients with alcohol problems and their families. She has to treat the “social and psychological wreck” that comes when one family member has an alcohol addiction. A crime commissioner from Devon and Cornwall police states that 50% of violence is alcohol-related in his area.

The film attempts to understand the reasons why alcohol use is at current levels, and offers some possible solutions. Alcohol is twice as affordable now as in the 1980’s and is more freely available than ever. This needs to be curtailed. Evidence suggests that alcoholic beverages were 61% more affordable per person in 2012 than in 1980, and the current number of licensed premises in England and Wales is at the highest level re corded in over 100 years. Licensed premises with off sales only alcohol licences have also reached a record high, more than doubling in number compared with 50 years ago. The evidence shows that price increases and restrictions on availability are successful in reducing alcohol consumption. More alcohol education in schools was highlighted as being necessary. The evidence suggests that alcohol education in schools can have some positive impact on knowledge and attitudes. Overall, though, school-based interventions have been found to have small or no effects on risky alcohol behaviours in the short-term, and there is no consistent evidence of longer-term impact. Alcohol education in schools should be part of the picture but other areas may prove more fruitful. The film suggests that parental and peer attitudes towards alcohol affect drinking norms, and these attitudes need to change. In multiple surveys, it has been found that the behaviour of friends and family is the most common influential factor in determining how likely and how often a young person will drink alcohol. Alcohol marketing was cited as a problem and it needs to regulated more stringently. Alcohol marketing increases the likelihood that adolescents will start to use alcohol and increases the amount used by established drinkers, according to a report commissioned by the EU. The exposure of children to alcohol marketing is of current concern. A recent survey showed that primary school aged children as young as 10 years old are more familiar with beer brands, than leading brands of biscuits, crisps and ice-cream.

corded in over 100 years. Licensed premises with off sales only alcohol licences have also reached a record high, more than doubling in number compared with 50 years ago. The evidence shows that price increases and restrictions on availability are successful in reducing alcohol consumption. More alcohol education in schools was highlighted as being necessary. The evidence suggests that alcohol education in schools can have some positive impact on knowledge and attitudes. Overall, though, school-based interventions have been found to have small or no effects on risky alcohol behaviours in the short-term, and there is no consistent evidence of longer-term impact. Alcohol education in schools should be part of the picture but other areas may prove more fruitful. The film suggests that parental and peer attitudes towards alcohol affect drinking norms, and these attitudes need to change. In multiple surveys, it has been found that the behaviour of friends and family is the most common influential factor in determining how likely and how often a young person will drink alcohol. Alcohol marketing was cited as a problem and it needs to regulated more stringently. Alcohol marketing increases the likelihood that adolescents will start to use alcohol and increases the amount used by established drinkers, according to a report commissioned by the EU. The exposure of children to alcohol marketing is of current concern. A recent survey showed that primary school aged children as young as 10 years old are more familiar with beer brands, than leading brands of biscuits, crisps and ice-cream.

David Nutt discussed research he conducted with colleagues, which assessed the relative harms of 20 drugs, including both harms to the individual and to others. They found that alcohol was the most harmful drug overall. Professor Nutt also covered the circumstances surrounding his sacking as government’s chief drug advisor; he claimed that ecstasy and LSD were less dangerous than alcohol, which led to his dismissal. This highlights the inherent tension between politics and science. Evidence can diverge from government policy and popular opinion, and scientists can lose their positions when reporting evidence that is politically unpopular. In my view, the reluctance of governments to implement evidence-based alcohol policies is frustrating; minimum unit pricing (MUP) being the latest example. Despite good evidence supporting how MUP can reduce alcohol-related harms, lobbying by the alcohol industry has halted its progress.

The film deals with the human cost of alcohol misuse, with personal stories of addiction permeating the film. Carrie Armstrong (who writes a blog discussing her battle with alcohol addiction), as well as Persia Lawson and Joey Rayner (who write a lifestyle blog ‘Addictive Daughter’), discussed the havoc alcohol caused in their lives, and explained how young men and women come to them for help with their own alcohol dependencies. Russell Brand talked about his own alcohol addiction during the film. He contends that his drug and alcohol use was medicinal and thinks that alcohol and drug addicts “have a spiritual craving, a yearning and we don’t the language, we don’t have the code to express that in our society”. Arthur interviewed Chip Somers of Focus 12, who talked about the low levels of funding to treat alcohol addiction. Only a small minority (approximately seven per cent) of the 1.6 million alcohol dependants in the UK can get access to treatment compared to two-thirds of addicts of other drugs.

Arthur recorded over 100 hours of footage of drinkers on nights out during the course of filming. He described it as follows: “As the sun goes down, society fades away and what emerges from the shadows is a monster of low inhibition, aggression and casual chaos”. He sums it up as us “going to war on ourselves. On one side is the police, the emergency services, the council and various groups of volunteers and on the other side you’ve got everybody else”. He was assaulted three times and witnessed multiple scenes of violence close up. His bravery is admirable – there were many scenes I found difficult to watch. The scenes of senseless violence were horrible to look at, as were the images of individuals who were so intoxicated as to be helpless and in need of medical attention.

The Q&A after the screening was quite illuminating. Arthur spoke about the reception the film has been receiving at home and abroad. The reception has been great in the United States, where the film has had successful showings at film festivals. The interest in the UK has been a little disappointing, however, which Arthur puts down to the reluctance of society at large to acknowledge our dysfunctional relationship with alcohol. Nevertheless, there has been positive feedback from viewers of the film. Many people have contacted Arthur to tell him how the film has opened their eyes to their own relationship with alcohol and prompted them to make a change. The audience was keen to engage in the conversation. One person, who has a family member with an alcohol addiction, said how important it is to raise awareness of these issues. Another person called for policy measures to be implemented such as MUP to curb use across the population.

Arthur came across as someone who is acutely aware of the damage alcohol is causing in the UK, and is doing what he can to raise the public’s consciousness about it. He has presented a unique look at booze Britain, in equal parts shocking, hilarious, sympathetic and thought provoking – a film we can all relate to. It was a very enjoyable and informative evening and I hope the audience took something away from it. I believe the arts and sciences need to work together to improve how knowledge is communicated. It was my hope that by showing this documentary, information on alcohol harms in society would be more accessible to a general audience. Change begins with the acknowledgement of new information that alters the view of ourselves and our behavior. It has been estimated that over 7 million people in the UK are unaware of the damage their personal alcohol use is doing. I believe the blame lies on both sides. Alcohol researchers need to communicate the harms of alcohol in more engaging and accessible ways and members of the general public need to seek out such information. All too often scientists get the reputation as being cold, boring, and amoral. Collaborating with filmmakers and other proponents of the arts on events such as the one I hosted can assist in changing that stereotype.