Author: Vicky Carlisle. Twitter: @Vic_Carlisle, Email: vicky.carlisle@bristol.ac.uk

On Wednesday 7th July 2021, I brought together key stakeholders with an interest in improving opioid substitution treatment (OST) from across the UK. This included people with lived experience, Public Health England staff, local authority public health practitioners, treatment service leads, pharmacists and academics. We discussed the findings of my recently completed PhD, and together we considered the next stages of developing an intervention to improve OST.

A summary of my research

For those not familiar with the topic, OST refers to the treatment of opioid dependency with either methadone or buprenorphine (alongside psychosocial support). Through my research, I wanted to understand what the key facilitators and barriers are to people ‘recovering’ in OST. To do this, I drew on both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. I found that loneliness, isolation and experiences of trauma and stigma were key barriers to recovery; whereas positive social support, discovering a sense of purpose and continuity of care were valuable facilitators.

Importantly, some factors appear to act as both facilitators and barriers to recovery in OST. For instance, I found that some service users used isolation as a form of self-protection (to shield themselves from negative influences), however this often left them feeling lonely and disconnected from the potential benefits offered by developing more positive social support networks.

Undoubtedly, the strongest barrier to recovery was stigma. Service users told me that they experience stigma from a range of sources, including from family and friends, healthcare professionals and members of the wider community. I found similar patterns in the literature review that I carried out (Carlisle et al, 2020). Stigma is like a stain where an individuals’ entire identity is defined by a single, negative attribute. In the case of OST, individuals may possess overlapping stigmatised identities of ‘OST service user’, ‘drug user’ and ‘injecting drug user’. Some will be further stigmatised due to experiencing homelessness, being HIV or Hepatitis C positive or through involvement in sex-work.

“I found that loneliness, isolation and experiences of trauma and stigma were key barriers to recovery”

Community pharmacies are one environment where service users report experiencing a great deal of stigma. Unlike customers collecting other prescriptions, many OST service users receive their medications (methadone/buprenorphine) through an arrangement known as ‘supervised consumption’. This means they must be observed taking their medication by a pharmacist to ensure that it is not diverted to others. This is often conducted in full view of other customers, despite guidelines which recommend that this takes place in a private room or screened area. This leaves OST service users open to the scrutiny of the ‘public gaze’.

My findings have several implications in relation to stigma. Firstly, OST service users receive poorer care than other members of society in healthcare settings, which may result in them avoiding seeking help from drug treatment and for other health conditions. Secondly, stigmatising OST service users makes community re-integration extremely challenging and this has been directly linked to individuals returning to drug using networks as it is somewhere they feel a sense of belonging. The ultimate impact of being repeatedly exposed to stigma is an internalisation of these judgements, resulting in feelings of shame and worthlessness – again impacting on individuals’ ability to seek help and develop supportive new relationships with others.

What we discussed during the workshop

Being able to present these findings to key stakeholders was a real highlight of my PhD work; it’s not often that you have the ear of so many invested and engaged individuals in one ‘room’ (albeit a Zoom room!). The findings of my PhD chimed closely with the experiences of those in the room and would be further reflected the next day when Dame Carol Black’s Review of Drugs Part 2 was published, which made specific reference to stigma.

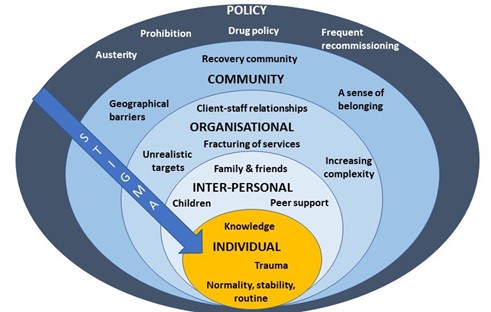

After I presented a short overview of my PhD findings, attendees spent time in small groups discussing how we might address OST stigma at each level of the socioecological system (see figure 1, above). A common thread that ran through each of the groups’ discussions was the importance of embedding interventions within trauma-informed frameworks. Attendees felt that increasing others’ understanding of the impact of trauma and ‘adverse childhood experiences’ (ACEs) may be a key mechanism by which to reduce stigma towards OST service users.

Indeed, a recent study found promising results in relation to this – that increasing the public’s awareness of the role of ACEs in substance use reduced stigmatising attitudes towards people who use drugs (Sumnall et al, 2021). Workshop attendees suggested that this outcome could be achieved through trauma-informed training of all individuals who might work with OST service users, such as pharmacists, the police and medical professionals, as well as those who work in healthcare settings, such as receptionists.

At the individual level there was a discussion about the way that stigma trickles down the socioecological system, resulting in self-stigma or internalised stigma. People felt that the best way to reduce this was to tackle stigma higher upstream first.

When thinking about reducing stigma in everyday inter-personal interactions, people highlighted the importance of using non-stigmatising language. For those who are interested (and I think we all should be!) the Scottish Drug Forum has published an excellent guide here.

Some excellent suggestions were made for reducing stigma that individuals experience in organisations such as pharmacies, hospitals and other settings. This is something that Dr Jenny Scott and I discussed in a recent article for the Pharmaceutical Journal (Scott & Carlisle, 2021). One attendee suggested the introduction of positive role-models within organisations who could be an exemplar of positive behaviour for others (a ‘stigma champion’ perhaps?). Training was identified as a key mechanism through which stigma could be reduced in organisations, including through exposure to people who use drugs (PWUD) and OST service users during training programmes. It was stressed however, that this should be carefully managed to ensure that a range of voices are presented and not just ones supporting dominant discourses around abstinence-based recovery.

Suggestions for improving community integration included increasing access to volunteering opportunities – something that people felt has been impacted by reduced funding to recovery services in recent years. It was also suggested that community and faith leaders could be a potential target for education around reducing stigma and understanding the impact of trauma, as these individuals may be best placed to have conversations about stigma with members of their communities.

Finally, there were some thoughtful discussions around the best way to influence policy to reduce stigma. The importance of showing policymakers the evidence-base from previous successful strategies was highlighted. Something that resulted in a lively debate was the issue of supervised consumption with arguments both for and against (this is also relevant at the organisational level). The group summarised that whilst diversion of medications was a risk for some, a blanket approach to supervised consumption and/or daily collections exposes individuals to stigma in the pharmacy, which leaves individuals vulnerable to dropping out of treatment. It was pointed out that supervised consumption policies were quickly relaxed at the start of Covid-19 restrictions – something that appears to have been done safely and with benefits to service users. It was also highlighted that supervised consumption in OST is inherently stigmatising, as users of other addictive drugs with overdose potential, such as other prescribed opioids and benzodiazepines, are not subjected to the same regulations. This sends a clear message to OST service users that they cannot be trusted. Other key suggestions were:

- Communicating with CQCs and Royal Colleges, who may be particularly interested in understanding how people are treated in their services.

- Drawing on existing stigma policies from other arenas e.g. mental health.

- Highlighting the fiscal benefits of reducing stigma to key decision makers.

- Tapping into plans for the new Police and Crime Commissioners, who have a trauma sub-group.

- Linking into work with ADDER areas, which may provide the evidence for ‘what works’.

What next?

I am now planning to apply for further funding to develop an intervention to reduce organisational stigma towards OST service users. The involvement of service users and other key stakeholders will be crucial in every step of that process, so I will be putting together a steering group as well as seeking out collaborations with academics internationally that have expertise and an interest in this area. I was really pleased to see that Dame Carol Black’s second report makes some concrete recommendations around reducing stigma towards people who use drugs. I hope therefore to be able to work with the current momentum to make OST safer and more attractive to those whose lives depend on it.

I’d like to extend my gratitude to all of the attendees at the workshop and to Bristol’s Drug and Alcohol Health Integration Team (HIT) for supporting this event. If you are an individual with lived experience of OST, an academic, or any other stakeholder working in this area and would like to be involved with future developments, please get in touch with me at vicky.carlisle@bristol.ac.uk or find me on Twitter at @Vic_Carlisle.

References

Carlisle, V., Maynard, O., Padmanathan, P., Hickman, M., Thomas, K. H., & Kesten, J. (2020, September 7). Factors influencing recovery in opioid substitution treatment: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/f6c3p

Scott, J & Carlisle, V (2021). A pharmacy resolution for 2021: let’s improve the way patients with addiction are treated. The Pharmaceutical Journal. https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/opinion/a-pharmacy-resolution-for-2021-lets-improve-the-way-patients-with-addiction-are-treated

Sumnall, H. R., Hamilton, I., Atkinson, A. M., Montgomery, C., & Gage, S. H. (2021). Representation of adverse childhood experiences is associated with lower public stigma towards people who use drugs: an exploratory experimental study. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 28(3), 227-239. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2020.1820450