By Jasmine Khouja (@Jasmine_Khouja), with contributions from Olivia Maynard, Suzi Gage, Gibran Hemani and David Troy

Alcohol and cigarettes may not seem out of place at a music festival; discussing the science behind alcohol, cigarettes and genetics may. This August, my colleagues and I from the MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) and Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group (TARG) at the University of Bristol took our research to the Green Man Festival 2015 (http://www.greenman.net/explore/areas/einsteins-garden/) which, though primarily a music festival, hosts the Einstein’s Garden where festival-goers can play, learn and converse about science. ‘Future’ was the theme so we took our ‘Bar to the Future’ to show where our research may lead.

Since the smoking ban, bars have been smoke-free but the growing popularity of e-cigarettes has sparked debate about their use indoors. Using an attention-grabbing demonstration (pictured right), we asked the public’s opinions on smoking and vaping. Our demonstration, in which cigarettes and e-cigarettes were smoked/vaped into the two separate glass tubes by means of a battery powered bed pump, shows a brown residue (tar) in the conventional cigarette tube where the e-cigarette tube is clear. Tar is not present in e-cigarettes making them, in one way, less harmful than traditional cigarettes.

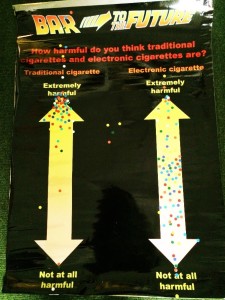

Members of the public shared their mixed opinions with us (pictured right) ranging from extremely positive to extremely negative. Many seemed concerned about the long term health effects of using e-cigarettes. Scientists are unsure of the long term effects of e-cigarette use because they have not existed long enough for these effects to be assessed and the rapidly changing devices make it hard for scientists to keep up. The wide spectrum of beliefs could reflect the inconsistency of information the public receive from the media; news sources reported Public Health England’s recent suggestion that e-cigarettes are 95% safer than conventional cigarettes and may eventually be prescribed on the NHS (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-33978603) which received backlash in a Lancet Journal editorial which also received media coverage (http://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/aug/28/public-health-england-under-fire-for-saying-e-cigarettes-are-95-safer). Opinion on conventional cigarettes however, was less divided. The public are clearly aware of the dangers despite many choosing to continue smoking. Opinions on vaping indoors showed a similar pattern to the views on e-cigarettes harm; worries over normalising smoking again and second hand vape were among the concerns despite no evidence suggesting inhaling second hand vape is dangerous. The exhaled vapour usually contains traces of nicotine and flavouring as well as an FDA approved substance used in most fog machines (propylene glycol). Though positive about the use of e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid as they contain fewer and lower doses of toxicants, they do still contain toxicants so we would not describe them as safe for non-smokers but they are safer than conventional smoking.

Members of the public shared their mixed opinions with us (pictured right) ranging from extremely positive to extremely negative. Many seemed concerned about the long term health effects of using e-cigarettes. Scientists are unsure of the long term effects of e-cigarette use because they have not existed long enough for these effects to be assessed and the rapidly changing devices make it hard for scientists to keep up. The wide spectrum of beliefs could reflect the inconsistency of information the public receive from the media; news sources reported Public Health England’s recent suggestion that e-cigarettes are 95% safer than conventional cigarettes and may eventually be prescribed on the NHS (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-33978603) which received backlash in a Lancet Journal editorial which also received media coverage (http://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/aug/28/public-health-england-under-fire-for-saying-e-cigarettes-are-95-safer). Opinion on conventional cigarettes however, was less divided. The public are clearly aware of the dangers despite many choosing to continue smoking. Opinions on vaping indoors showed a similar pattern to the views on e-cigarettes harm; worries over normalising smoking again and second hand vape were among the concerns despite no evidence suggesting inhaling second hand vape is dangerous. The exhaled vapour usually contains traces of nicotine and flavouring as well as an FDA approved substance used in most fog machines (propylene glycol). Though positive about the use of e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid as they contain fewer and lower doses of toxicants, they do still contain toxicants so we would not describe them as safe for non-smokers but they are safer than conventional smoking.

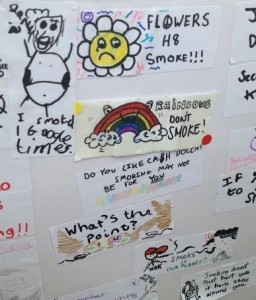

The children of Green Man got involved by designing cigarette packaging warning labels. Here are a few of the designs placed on our giant cigarette packet which could show the future of cigarette health warnings.

Alcohol

Calorie information is now placed on food and soft drinks bought at supermarkets but rarely placed on the packaging of alcoholic drinks. Calls from public health officials and policy makers could see calorie content on labelling made mandatory. By asking the public to guess how many calories were in lager, whiskey, alcopops and wine it became apparent that the public have limited knowledge when it comes to the calorific content of alcohol. This is unsurprising as calorie content varies across brands, strength and size of alcoholic drink. Without the information being provided, it is difficult to know how many calories are in your drink (some information can be found on the drink aware website, https://www.drinkaware.co.uk/understand-your-drinking/unit-calculator).

Straight glasses may be used more in bars rather than curved glasses in the future. To demonstrate the effect of this we asked festival-goers to half fill a curved and a straight glass with water. The majority of festival-goers struggled to find the half-way point on the curved glass yet found it relatively easily on the straight glass. This finding has been shown in the lab too; people perceive the half-way point to be lower than it is on a curved glass and consume a half pint 4 minutes faster in a curved glass than from a straight glass and drink 1 minute slower from glasses marked with volume information displaying where the ½, ¼ and ¾ points are. By simply adding volume information to glasses and using straight instead of curved glasses the public may reduce their drinking speed meaning they drink less over the course of their drinking session.

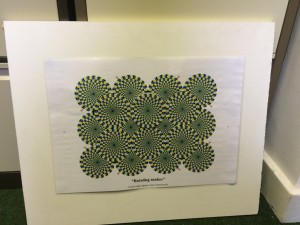

We also shared some future research which involves the Rotating snakes illusion (pictured right). When viewing this illusion the motion perception areas in the brain are activated meaning the viewer perceives the snakes as rotating. We hypothesised that if festival-goers had consumed alcohol they would see less or no rotation due to their motion perception being impaired. Though we did not observe this, there was a lot of variation in quickly the public saw the snakes rotate even if they hadn’t consumed any alcohol. This information will be useful when designing our future lab studies so that each participant is tested with and without having consumed alcohol rather than comparing alcohol consumers to non-alcohol consumers.

We also shared some future research which involves the Rotating snakes illusion (pictured right). When viewing this illusion the motion perception areas in the brain are activated meaning the viewer perceives the snakes as rotating. We hypothesised that if festival-goers had consumed alcohol they would see less or no rotation due to their motion perception being impaired. Though we did not observe this, there was a lot of variation in quickly the public saw the snakes rotate even if they hadn’t consumed any alcohol. This information will be useful when designing our future lab studies so that each participant is tested with and without having consumed alcohol rather than comparing alcohol consumers to non-alcohol consumers.

Genetics

A popular part of our stall was the genetics of table football. This was no ordinary game of table football, each team was made up of a genetics and an environmental player to demonstrate how our genes and environment affect the person we are in the future. The genetics players rolled a dice to decide their genetic predispositions (e.g. to alcohol dependence) which represented the element of chance in who we are. This related to an advantage or disadvantage in the game (e.g. holding a cup while playing). The environment player then picked a card (representing the element of choice in our environment) giving the player an advantage or disadvantage. The players then battled it out. The team who scored the first goal got to pick a controlled environment card; they could either lose one of their disadvantages (e.g. put the cup down) or choose to disadvantage the other team before continuing play. The game sparked discussions on how neither your genes or environment solely determine who you are, it is a team effort.

Festival-goers also tried PTC (Phenylthiocarbamide), which has a rare property; 70% of people experience a bitter taste but 30% of people taste virtually nothing when they try this chemical due to their genetics. After asking festival-goers to lick a PTC strip they were asked if they liked four bitter foods. We expected to find that those who can taste PTC are more sensitive to bitter tastes and therefore like bitter tasting foods less than those who cannot taste PTC. Information like this could be used in the future to help people decide what alcoholic drinks may taste better to them. We found that PTC tasters were as likely to like bitter tasting foods as those who can’t taste PTC.

After three days of games and discussions with the public, our gazebo proved no match for the Welsh weather and was left broken beyond repair after heavy rainfall. We were forced to shut down the stall a day early but for those who missed out, we hope to see you next year!